It's official: junk pop has taken over the charts. Since the early 1990s,

the proportion of stars created on TV talent shows and manufactured boy and

girl bands has risen year on year - to over two-thirds of No 1 singles.

It's official: junk pop has taken over the charts. Since the early 1990s,

the proportion of stars created on TV talent shows and manufactured boy and

girl bands has risen year on year - to over two-thirds of No 1 singles.

FolkWorld Issue 32 12/2006; Column by Walkin' T:-)M

It's official: junk pop has taken over the charts. Since the early 1990s,

the proportion of stars created on TV talent shows and manufactured boy and

girl bands has risen year on year - to over two-thirds of No 1 singles.

It's official: junk pop has taken over the charts. Since the early 1990s,

the proportion of stars created on TV talent shows and manufactured boy and

girl bands has risen year on year - to over two-thirds of No 1 singles.

That's The Trouble with Music, says Mat Callahan: Vanity, boredom and sex are by far the most common themes in pop music. Clearly, the function of this is to divert attention, to provide escape and to encourage narcissism; time-killing in place of timelessness and actual experience-based emotions. Popular once meant originating in the populace. Today the music industry manufactures the products and spends enormous amounts of money making them popular. It now means widely consumed.

EMI cannot make music, but it can make celebrity. It is of no value to EMI that a group is playing for a packed house of excited concert-goers, or that a particular songwriter has a loyal following. These audiences do not constitute a market. Until that group or songwriter is transformed into a media phenomenon - a name - they can never sell the number of units that is profitable. Until that audience is transformed into a market for a product - not just people with intelligence and feelings - that can then be manipulated by the record company, it is not worth the investment.

Critical standards by which to evaluate quality have been replaced by

another: how many units have been sold.

Similar to the replacement of essential nutriment by junk food.

Capitalism has intensified its pursuit of the commodification of everything.

Life and experience must be made into an object for which you can be forced to pay.

According to Mat, several tactics have been employed:

Capitalism has intensified its pursuit of the commodification of everything.

Life and experience must be made into an object for which you can be forced to pay.

According to Mat, several tactics have been employed:

1. Replace quality with celebrity.A true analysis (so it is for film and literature). However, there is no need to give in to anti-music, muzak, corporate music, fake music, placebo music, or the sonic equivalent of fast food. Anti-music poisons just as air pollution does. In fact, it is air pollution! Mat suggests to return to the question of criteria. Good music is that which:

2. Place music into every conceivable public and private space, making its prevalent use sonic adornment.

3. Produce enourmous quantities of music and flood the world with it.

4. Consolidate control of all distribution and promotion.

5. Simplify and repeat.

1. Engages the listener's attention, holding it for the duration of the piece - in effect, suspending time.Mat Callahan had been the leader of the Looters, who in the 1980's were instrumental in establishing the world-beat musical movement on the US west coast. He knows what he's talking about and he writes with passion and heart. He has a lot to say, critical thoughts on internet file sharing, copyright and royalties, and folk music in particular. He raises questions that are supposed to threaten big business, managers of record labels and agencies, and their whores and dope dealers alike.

2. Transports the listener to an imaginery place, without leaving the physical place in which the music is heard (we speak of being moved.)

3. Evokes emotional response without relying on visceral effect - except as required by the music itself. (This mainly concerns timbre and volume.)

4. Introduces novel elements in one of four ways:

- never before or rarely heard

- unusual, personal expression unlike any or most others

- rare technical virtuosity of performance, arrangement or composition

- infuses the old with new enthusiasm and perspective making it new again

5. Invigorates thought about music either before, during or after the performance in one of three directions:

- wanting to hear more

- wanting to know more

- wanting to do more.

Decide yourself, is this what you want?

Each of us (at least 10 million) will have one Robbie Williams CD to satisfy our musical needs. All other musicians in the world will have to perform our own music to each other, backstage, while preparing to go out and perform covers of Robbie Williams songs to the audience, who now only wants to hear those songs over and over again!If you don't want this, go get the book for a start! Turn phony music off! Stop listening to it! Start rejecting what is being advertised! Challenge the assumption that what is famous is good! Doubt the quality of that which is already well known! Seek to make your own discoveries of hidden treasures!

Then, if we awoke tomorrow to find that the music industry had disappeared would it make any difference to music? - Mat says: NO!

The making of music is in no danger of extinction. Music is a collective activity that produces active collectivities. It is not only - or mainly - a commodity to be consumed. Turning off the soundtrack of idiocy will enable, and is enabled by, turning on of the joy music provides. Of this there can never be too much. Always just enough.Food for thought. Keep this in mind while we're heading off for some lighter entertainment.

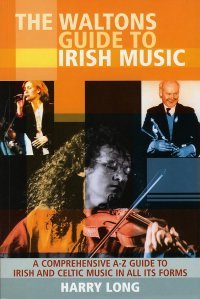

Every once in a while a new guide book about traditional Irish Music is thrown upon

the market (see -> FW#20,

FW#27,

FW#30,

FW#31).

Some have been in print for a couple of years and might be considered a bit

out of date. Now time has come for another one to update the tradition.

Some have been in print for a couple of years and might be considered a bit

out of date. Now time has come for another one to update the tradition.

Harry Long is teaching and playing the whistle in the Meath-based band Coscan. He started writing The Waltons Guide to Irish Music in 1995 when he finished his PhD in Medieval Irish History and Archaeoloy.

Waltons: Ireland's best-known music company, Waltons was founded by Martin Walton (1901-1981). Walton, a Feis Ceoil winner on violin, had been a member of na Fianna and at the age of fifteen had acted as a courier between the GPO and Jacob's Mill during the Easter Rising of 1916. During a period of internment at the Ballykinlar prison camp in 1919 he organised a orchestra there, in keeping with the Irish provisional government's emphasis on Irish culture and education. In 1924 he founded the Dublin College of Music in North Frederick Street. From there he developed a retail music shop, began manufacturing Irish harps and uilleann pipes, and set up a publications division specialising in Irish songs and ballads written or collected by Peadar Kearney (composer of the Irish national anthem), Leo Maguire, Joseph Crofts and Delia Murphy among others, as well as publishing a tutor for uilleann pipes (by Leo Rowsome [-> FW#26]) and the Edward Bunting and Francis O'Neill collections. In 1952 Walton set up the Glenside Record label, recording and publishing both original and traditional Irish songs and ballads. Waltons' national reputation grew substantially during the period of the Waltons Radio Programme, a sponsored programme broadcast on Raidió Éireann from 1952-1081. Broadcast on Saturday afternooons, the programme became a national institution, its slogans - including If you feel like singing, do sing an Irish song - now embedded in the national collective memory.

An A-Z guide from Altan

(-> FW#31)

and Australia (-> FW#31)

to the Waterboys

(-> FW#31),

and Dennis Zimmerman (-> FW#27).

Just another example, since celebrating its 40th anniversary in 2006:

Armagh Pipers Club, The

Founded in 1966 by a group of music enthusiasts including Brian and Eithne Vallely

to promote the playing of the uilleann pipes and traditional music generally.

Although not affiliated to any national organisation, the Armagh Pipers' Club has

established a considerable reputation over the years and its members play a variety

of instruments in addition to the pipes, including flute, fiddle, tin whistle,

concertina and accordion. They have published several tutor books (including uilleann

pipes, tin whistle and fiddle) as well as collections of songs for children. They also

organise an annual festival (held in November), the William Kennedy Festival of Piping

[-> FW#29],

in honour of an 18th-century blind piper of that name. Website:

www.armaghpipers.com.

We get over 900 entries: musicians, groups, recordings,

types of music, singing and dancing,

instruments, collectors, organizations, festivals and summer schools.

Harry Long's ten years work features a lot of younger artists such as

McGoldrick

(-> FW#31),

Kelly

(-> FW#23),

Mayock

(-> FW#26),

and groups such as Flook

(-> FW#31),

and Kila

(-> FW#30).

There are curiosities such as

bronze-age horns (-> FW#31) and Irish music in

Argentina.

Harry Long puts his personal stamp on it. I wonder sometimes why HE deserves such a lengthy entry and SHE that short one. But anyway. As with all those guides and companion, Waltons has its errors and its weaknesses - e.g. it is Capercaillie, not Cappercaillie (-> FW#29).

But that's rather peanuts. What's really missing? Well, at least I didn't expect

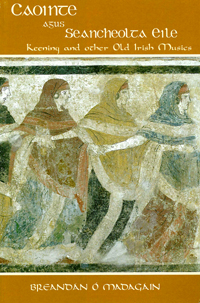

fo find an entry on Breandán Ó Madagáin.

Dr Madagáin had been a Professor of Irish at Galway University from 1975-97.

His special field of work is the oldest musical traditions of Ireland, especially that

of the caoineadh (i.e. keening).

Breandán Ó Madagáin explores the different types of

ancient Irish singing that are, I guess, not usually associated with Irish folk music.

In the end his book is not too scholarly.

This is made entirely clear by the surplus CD, including pieces such as

the 17th century "Elegy for Úna Bhán" (->

FW#24,

FW#29),

"Here beside the Maigue"

(which is the tune of "An raibh tú ar an gCarraig?" ->

FW#21,

FW#21,

FW#22,),

the exile song "Slán le Máigh" (Farewell to the Maigue

-> FW#19),

the drinking song "(An) Buachaill Caol Dubh"

(The Thin Dark Fellow -> FW#24),

and the well-known love song "The snowy-breasted pearl".

(Well, it's well-known, but seemingly rarely recorded.

At least, I didn't find one.)

And much, much more.

Keening and Other Old Irish Musics

is a bilingual publication, in English and Irish,

that contains forty examples of this and related matter.

Keening and Other Old Irish Musics

is a bilingual publication, in English and Irish,

that contains forty examples of this and related matter.

In pagan times, and for long afterwards, it is most likely that keening had

a supernatural ritual function: to transfer the spirit of the deceased from

this world to that of the spirits.

With the passage of time there came a change of emphasis in the function of

the keen: to that of emotional release.

In contrast, the elegy (marbhna) was

a carefully wrought poetical composition

by the chieftain's bardic poet for performance at a commemorative ceremony.

Ireland can boast of Ossianic lays and syllabic hymns. There had even

been work songs, so heavy or monotonous work became entertaining.

Unfortunatly, not many have come down to us, since their widespread practice declined

before collectors recorded them.

The lone keener sang her verse chant-like, many syllables on the same note,

with little ornamentation and ending on a falling cadence.

Each district had its own version, which all the local people would know

from constantly hearing it.

A significant feature of the work songs, both in Irish and in Scottish Gaelic,

were the vocables, especially in the refrains. A well-known example is the

refrain of the smith's song: Ding dong didilum. These nonsense syllables

are usually taken to be for the sake of the rhythm, accentuating it. It could

well be, however, that they have a more fundamental meaning, echoing the magic

origin of the work songs. It is clear from international comparison that work

songs were an essential part of the magic ritual performed to ensure the success

of the work. The impatient reply of an old lady in the Isle of Barra when I asked

her expressly why she sang the churning song at the buttermaking was: To get

more butter, of course. The formula used in magic ritual has typically been

unintelligible (purporting to be the language of the spirits), repetitive and

incantatory, the music being the means of communication with the spirit world.

It appears likely that this refrain echoes the original charm, and that the

meaningful verses were a later development.

If it is true that the work songs echo superstitious practices,

lullabies also had such a function,

namely to protect the baby from being taken away by the fairies.

Love songs, on the other hand, had a common European structure:

It is most likely that this structure came into Ireland with the love songs

of the French tradition (with the Anglo-Normans) and those sung in English

(by the English and Scots). The Irish retained the basic structure in their

own compositions, very different from the putatively earlier native

music mentioned above: that of keens and elegies, work songs and lullabies.

The music of the love songs was also used for religious songs,

political songs such as the aisling songs,

and macaronic songs, sung partly in Irish, partly in English.

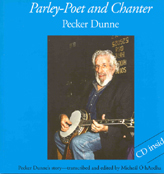

One entry I deeply missed in Waltons, regards the

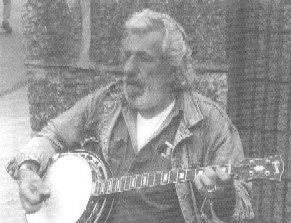

Pecker Dunne:

one of Ireland’s best known and one of the last of the travelling

traditional musicians and balladeers.

Pádraig 'Pecker' Dunne had been born in a horse-drawn wagon in

1932 (not 1952 as the book has it), while stopping in Castlebar, County Mayo, in the west of Ireland.

One entry I deeply missed in Waltons, regards the

Pecker Dunne:

one of Ireland’s best known and one of the last of the travelling

traditional musicians and balladeers.

Pádraig 'Pecker' Dunne had been born in a horse-drawn wagon in

1932 (not 1952 as the book has it), while stopping in Castlebar, County Mayo, in the west of Ireland.

Today people often describe the old way of life that Travellers had as a very

romantic one. We were all happy-go-lucky people without a care in the world.

Sure, there was always somehing special about travelling the tóhbar.

But it was not at all fun and games. There was a lot of hardship too especially

in the winter time. The lads would sleep in a tent and sometimes there was only

straw between us and the wet ground. The dampness would get to you.

Outside some towns we were forced to camp on waste ground or near dumps. This

was very bad for the health and there was the danger of rats and disease.

It wasn't all flowers and roses when we were young. A lot of people were

prejudiced against us because we were Travellers.

When they would see us coming it was like we were the Red Indians or something.

His dad was a travelling musician and these were the family ways:

My father told me that there was only one way that I was going to get a living

and that was with my fiddle and my music.

He showed Pecker the fiddle and said:

There you go, there is your living. If you don't play it you will go hungry.

It's that simple.

However, Pecker changed course and took up the banjo instead:

There was more of a jazzy swing to it. And I liked to sing and you can sing with a banjo

where you can't with a fiddle.

Ted Furey used to come down because he was teaching

young Johnny Keenan.

Every time I heard the twang of Ted's banjo I used

to sneak under the wagons and listen to him.

People have this image of banjo-players that they somehow aren't real musicians. The reason is that banjo-playing originated in the Deep South of America amongst the country people, the people that were sometimes called hillbillies. The thing that I love about the banjo is that it is the instrument of the outsider, the fella who is different, the person who isn't just willing to go along with everything for the sake of it but who is willing to challenge things if they aren't right.Pecker travelled the length and breadth of Ireland, England, America and even Australia. He entertained both travellers and settled communities, busked at fairs, played in pubs and prestigious concert halls. It was travelling musicians who started the music scene in pubs like Donoghues (-> FW#9). Both BBC and RTE did documentaries about his life, and Pecker played alongside Richard Harris and Stephen Rea in the film "Trojan Eddie".

Woody Guthrie [-> FW#26] was an outsider. He used his music to challenge things. His time on the road and his history was very like my own. Like myself, he used the music to fight his way through the world. That was his weapon. Like myself too, he wrote songs about the road, about the travelling life and what it was like to be treated by some people as an outsider. I am an outsider too. I use my music and my songs to challenge people in Ireland about the way Travellers are treated. I have also used it to celebrate the richness of Traveller music and Traveller culture.

Parley-Poet and Chanter - Pecker Dunne is told by the Pecker Dunne himself in his very own voice, buskers' cant, and had been transcribed and edited by Micheál Ó hAodha of the University of Limerick. He gives an account of the tinker's life, memories of the road, and, maybe more important for us, memories of fellow musicians like Margaret Barry, Luke Kelly and The Dubliners (-> FW#23):

I taught them a few things, too. I thought they were a bit too stiff in their playing at the start. You need to be a bit flexible to get to the heart of the music. Luke Kelly was a grand fellow and a great musician. I would rate him as one of the best there ever was. He used to say, there is only one way to sing a song and that is belt it out. Don't try to polish it too much. Just belt it out. That is what a song is for. A good ballad is worth belting out. And I believe that he was right about that. Those old ballads aren't supposed to be sung in a low polite voice. You have to put that bit of feeling and emotion and power into it.Jim McCann (-> FW#18) says about Pecker: That is what we are trying to be. And Christy Moore (-> FW#3) adds: Traveller music was a big influence on my style when I was starting out as a folk-singer. What more praise can a musician get.

A CD is attached to the book, featuring his original songs "Wexford Town", "Sullivan's John" (his most famous song and he wrote it when he was only eleven), "A Tinker's Lullaby", "Ballybunion by the Sea", "In a Tinker's Caravan", and Pete St John's "Danny Farrell". Unfortunatly, not Pecker's "The Last of the Travelling People":

I am an old timer, I've travelled the road,

A hotel is me jungle, the cab's me abode.

Oh, me name it is Paddy, I'm called Pecker Dunne

My cry, it is All for all, one for one.

With me Bajo and fiddle I yarn in song,

I sing to all people who do me no wrong.

From Belfast to wexford, from Clare to Tralee,

A town with a pub is a living for me.

Another entry I missed in Walton's is fiddler Josephine Keegan.

She might not be the most famous of performers, but she is well respected since being a prolific

writer of tunes in the traditional vein.

Many of her tunes have been played at sessions for so long that they are assumed to be traditional.

Tommy Peoples (-> FW#25) recalls:

Many of her tunes have been played at sessions for so long that they are assumed to be traditional.

Tommy Peoples (-> FW#25) recalls:

On occasions, at sessions, on hearing particular tunes that appealed to me, I would ask the player about the tune. Surprise, surprise, several times they turned out to have been written by Josephine Keegan, but were already part of the tradition.Josephine had been born in Dundee, Scotland, in 1935, but the family returned to South Armagh, northern Ireland, when she was four. She started with the fiddle at six and frequently broadcasted at RTE with piano player Sean O'Driscoll. I so admired his playing that I had to try it out for myself. She became one of the most renowned accompanists, playing with Joe Burke, Finbarr Dwyer and Sean McGuire. After 15 years of accompanist she returned to the fiddle and became a terrific writer of tunes.

Finally, a collection of her tunes has been published. The Keegan Tunes is a collection of 80 of Keegan's compositions (plus some Carolan tunes and dance tunes from the South Armagh area). The quality may be judged by the number of tunes which have been picked up and recorded by others. Reels such as "Gates of Mullagh" (-> FW#18), "Square at Crossmalen" (-> FW#25), and "Yew Tree" (-> FW#27). The Irish name for Newry is Iubhair Cinn Tragha (The Yew Tree at the head of the strand). Jigs like "Only for Barney" (-> FW#26, FW#27), Barney's been the pet name for her daughter during her days of watching The Flintstones. Or the hornpipe "Fiddler's Green" (-> FW#27).

A double CD set, "Lifeswork," is sold separately. It includes performances of almost all these tunes in the house dance style. In the book, the music is presented alongside notes on the tunes, photos, illustrations, a biography and some of Josephine's memories:

On one occasion I remembered Rory [Kennedy] asked my Dad to stand in for John Joe Gardiner - [the Siamsa Ceili Band's] flute player, who was not well. He was pleased to do this but came home a little defeated as Rory had insisted on paying him for his efforts. It was the only time he had ever taken money for playing music and felt somewhat of a traitor to the cause.Compare that to a hipphopper whose credo is: Get rich or die tryin'.

Well, I looked very hard to find an entry in Walton's to introduce the next subject.

Eventually I found one (that goes something like this):

Hands On Scottish Tin Whistle is a step by step guide to learn and play the

(Scottish) tin whistle .

If you don't play any instrument until now,

the tin whistle is great to start.

It begins with "Mary Had a Little Lamb" and "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star".

In the end you should be able to play

"The Hen's March o'er the Midden" (-> FW#24)

and the "High Road to Linton"

(-> FW#20).

You are about to learn the very basics, arpeggios, slurring, grace notes, rolls.

You don't have to read music, alternatively you can play using a fine number system.

I searched out my own worn-out whistle. Eventually I found it, and after browsing

through this book, I was able to play the odd tune again in a short matter of time.

Now, if you mastered the tin whistle, we can continue with fiddle and pipes.

Susie Petrov observed:

For example, the reel "High Road to Linton" (see above)

is the tune to the songs "Bodachan a' Mhirein" and "Got a Can of Beer".

There are words to tunes such as

"Ewe With The Crooked Horn" (-> FW#2,

FW#20,

FW#24),

"Jenny Dang The Weaver" (-> FW#24,

FW#26),

"Lanigan's Ball" (-> FW#24,

FW#25),

"My Love Is But A Lassie Yet" (-> FW#25,

FW#25),

"Rattlin' Roarin' Willie" (-> FW#22,

FW#22).

Rabbie Burns is featured twice,

with "I Have A Wife Of My Own" (-> FW#27) and

the Scottish national anthem "A Man's A Man (For A' That)" (->

FW#15,

FW#31).

Besides those popular tunes, the authors offer much more interesting details.

"Whistle O'er the Lave O't" (-> FW#24)

is played for dancing the Sean Truibhas, a dance devised to celebrate

the end of the proscription of the tartan in 1782.

The popular "Lewis Bridal Song" aka

"Mairi(e)'s Wedding" (at least very popular with German bands ->

FW#18,

FW#29,

FW#22,

FW#25)

was composed by Johny Bannerman for Mary McNiven and sung originally in Gaelic

for the Mod in 1935. Sir Hugh Robertson translated the song into English in 1936.

Mary, herself celebrated her 90th birthday on Islay in 1998.

"Merrily Danced the Quaker's Wife" comes with some bawdy words:

Brighton-based singer-songwriter Nick Burbridge

is best known to FW readers as the head of McDermott's 2 Hours (-> FW#29).

His second collection of poetry All Kinds of Disorder

is the follow-up to 1994's "On Call."

Nick already named his last CD "Disorder".

He himself said: I've never been entirely stable.

Woman, you have single-handedly caused me more damage than all my enemies together.

It's not just the women, the entire world had gone wrong for the poet.

The disenchanted youth (the singer?) remarks:

I see now my career's unfolded to the letter,

though no emission on my sheets is of evolutionary consequence.

Nick's poetry, so far I can really judge English-language poetry as a non-native speaker, is

passionate and furious, dark and bittersweet, confusing and bizarre.

I give you one example, chosen just because of its shortness, a poem called "Coalition":

Whistle (feadóg):

In Ireland, the Brehon Laws mention whistle players as early

as the 6th or 7th century. The earliest physical remains of whistles were found

in Christchurch Place, Dublin. These date from the 13th century and are made of

bird bone.

Until recent decades, the English-made Clarke tin whistle, first

manufactured in 1843, was the standard type. It consists of a cone-shaped piece

of tin with a wooden fipple in the mouthpiece. In the past 30 years, cylindrical

whistles made of brass with plastic mouthpieces have become more common. The

British-made Generation was the first to be mass produced and still make

the widest variety of whistles in different pitches. Tin whistles are also made

in Ireland now, most notably the Feadóg and Waltons type.

Until recent decades, the English-made Clarke tin whistle, first

manufactured in 1843, was the standard type. It consists of a cone-shaped piece

of tin with a wooden fipple in the mouthpiece. In the past 30 years, cylindrical

whistles made of brass with plastic mouthpieces have become more common. The

British-made Generation was the first to be mass produced and still make

the widest variety of whistles in different pitches. Tin whistles are also made

in Ireland now, most notably the Feadóg and Waltons type.

Donncha Ó Briain, Seán Potts, Micho Russell, Seán Ryan, Mary Bergin,

Vinny Kilduff, Joannie Madden, Brian Hughes and Conor Byrne are among the most

famous tin whistle players of recent decades. Many uilleann pipers, such as

Brenda Monaghan (formerly of Different Drums of Ireland [->

FW#21]), Liam O'Flynn,

Darach de Brún, Joe McKenna, Paddy Maloney, Paddy Keenan [-> FW#30] and Brendan Keenan

are also fine whistle players.

Two fine young whistle players who have released albums in recent years are

Gavin Whelan and Breda Smyth [see review in this FW issue].

One morning, I was playing a tune, "The Drunken Piper" on the piano. As a dance

musician, I knew the tune as a reel. A 12 year old girl came up to me and said,

I sing that song, but it's a bit different the way I do it. She proceeded

to sing the most beautiful rendition of "Far am Bi Mi Fhin" that I have ever

heard. Here was the first tune that I had encountered that existed in several

traditions: as a pipe march, as a dance tune and as a Gaelic song. Which came

first? Did it matter? Were there other tunes that also existed in various traditions?

The answer is, yes!

Susie Petrov (US) and Christine Martin (Isle of Skye)

identified songs from the Scottish tradition, both in English and Gaelic,

whose tunes are currently played as instrumental music.

Susie Petrov (US) and Christine Martin (Isle of Skye)

identified songs from the Scottish tradition, both in English and Gaelic,

whose tunes are currently played as instrumental music.

Come tell me dame, come tell me dame

Christine says: The more our collection grew it the more obvious it became that no matter

whether you are a singer, fiddler, piper or dancer Scottish music is "a' connected."

Hence the title. We're A' Connected is a collection of

95 (published and unpublished) traditional Scottish songs with their dance tunes.

Lyrics plus instrumental settings,

arranged in keys that should be ideal for singers and both fiddlers and pipers

(Dougie Pincock, -> FW#8,

FW#17,

FW#27,

FW#28,

produced the pipe versions).

However, any other instrument should be welcome as well.

It's great stuff, a history lesson as instructive as possible. And it's fun anyway.

My dame come tell me truly,

Wat length of tool when used by rule

Will serve a maiden duly.

The auld dame claw'd her wanton tail

Her wanton tail sae ready

I learned a song in Anandale,

Nine inch will please a lady.

We hae tales to tell,

And we hae sangs tae sing;

We hae pennies to spend,

And we hae pints to bring.

Call yourself ally or enemy;

I read somewhere:

Had Patricia Highsmith's psychopathic hero Ripley gone and lived in Sussex and joined a folk band he might have written these poems.

Yeah, could be the folk-singer's and storyteller's equivalent,

now free from the restraints of the song metre.

The volume comes complete with a five track sampler CD of readings arranged with music and effects by the Levellers’ Jon Sevink (->

FW#31). It provides a dramatic soundtrack,

displaying that these poems have great musicality as well.

That is what we would expect from a matured songwriter.

I will not lift my eyes

from the child's corpse

pressed into my arms

to trace causes

branded across night skies.

Hold this focus

and burden;

drenched in tears

and trembling with

the weight of our sorrows

how will we fight?

Cheerio, see you here again, same place, T:-)M.

Burbridge, Nick. All Kinds of Disorder.

Waterloo Press, Hove, 2006, ISBN 1-902731-29-8, 39pp, UKŁ5,00 (including CD;

www.burbridgearts.org).

Callahan, Mat. The Trouble with Music.

AK Press, Oakland, 2005, ISBN 1-904859-14-3, 245pp, US$18.95 (UKŁ10,00); foreword by Boff Whalley, Chumbawamba (see CD review in this FW issue).

Gray, Fran. Hands On Scottish Tin Whistle.

Taigh na Teud, Isle of Skye, 2005, ISBN 1-871931-789, 43pp, UKŁ7,90.

Keegan, Josphine. The Keegan Tunes - A Selection of Traditional Irish Music Composed by Josephine Keegan.

Ceol Camloch,

125pp, €29,00 (double CD available).

Long, Harry. The Waltons Guide to Irish Music - A Comprehensive A-Z Guide to Irish and Celtic Music in All Its Forms.

Waltons, Dublin, 2005, 427pp, €17,95.

O hAodha, Micheal. Parley-Poet and Chanter - Pecker Dunne.

Farmar Books, Dublin, 2004, ISBN 1899047131, 118pp, €14,99 (including CD).

O Madagain, Breandan. Caointe agus Seancheolta Eile - Keening and Other Old Irish Musics.

Clo Iar-Chonnachta, Dublin, 2005, ISBN 1-902420-97-7, 156pp, €16,00 (including CD).

Petrov, Susie, and Christine Martin. We're A' Connected - 95 Traditional Scottish Songs with their Dance Tunes aranged for Fiddle and Pipes.

Taigh na Teud, Isle of Skye, 2005, ISBN 1-871931-83-5, 104pp, UKŁ12.

T:-)M's Night Shift (FW#31)

German Titles

All material published in FolkWorld is © The Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content of the linked external websites.