FolkWorld #73 11/2020

T😷M's Night Shift

»Martyn lived his life the same way he made his music, improvising as he went, with no safety net, admirable in one sense and impossibly irresponsible

in another. He tore through it, scattering brilliance and destruction in his wake.«

Part of the poet or songwriter’s job is to say what we’re afraid to admit. To give voice to feelings that would otherwise remain

unspoken or unsung. To give others permission to sing what their hearts want to say. To let us dream out loud. To build a bridge over

our fears. And to remind us what an impossibly beautiful gift it is to be alive on planet Earth.

I’ve heard that the flap of a butterfly’s wings might affect the course of a hurricane. And I know

that words and deeds ripple out in ways we can’t foresee or discern. Whether we know it or not, we’re changing the

world... [These songs] don’t lead to a lot of answers, but I hope they raise some of the right questions. These words and

these songs are just pebbles in the pond. However the ripples reach you, I’m grateful. ♥

Musically, it is a stringband album (with a fiddle, because the fiddle is the electric guitar of acoustic music). He even

paid a couple of fiddlers who don't appear on the album at all (but I figure fiddleanthropy really can’t be bad for the world).

Besides his original songs expounding his philosophies and politics, Scott covered Richard Blakeslee's movement song from the 1940s, "Passin' Through":

It fit with a thread I saw running through this collection, about the world as a proving ground for souls. I added a new verse for

another hero whose story isn’t well enough known: the Chilean poet, singer, theatre director, teacher, and activist Víctor Jara.

The album closes with an instrumental tune, "Right to Roam," hinting at the verse -

The other day when I went walking I saw a sign there, said No Trespassing... -

from Woody Guthrie's "This Land is Your Land" which didn’t get sung when I learned it in school:

It got its name from the freedom to roam, also

known as “everyman’s right”––the right of public access to certain

kinds of land. The idea that “I’m just trying to get over there” would take

precedence over “get off my lawn” struck me as pretty profound. It

kind of reminds us, again, how so much of what we take to be the

immutable order of the world is just a matter of arbitrary convention.

I mean, who decided that somebody could own land in the first place?

Most indigenous cultures around the world don’t think so.

Scott Cook, Tangle of Souls. Own label, 2020 (CD/Book)

Chris Regez, The Songwriter: Following The Sound Of Love.

2020, ISBN 978-1-09831-143-8, pp368, €16,67 (www.der-songwriter.com)

Nathaniel Webb, Decades: Marillion In The 1980s.

Sonicbond Publishing,

2020, 978‐1‐78952‐065‐1, pp160, €17,60

Nathaniel Webb, Decades: Marillion In The 1980s.

Sonicbond Publishing,

2020, 978‐1‐78952‐065‐1, pp160, €17,60

Graeme Thomson, Small Hours: The Long Night of John Martyn.

2020, ISBN 978-1-787600-19-5, pp265, US$28.00 UK£20,-

A man's life in one sentence. No, it needs hundreds of pages to even get a glimpse of an artist's personality, not even considering his art and music.

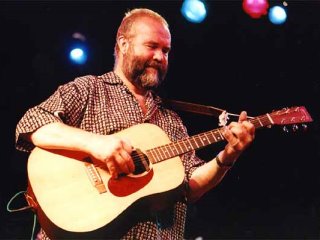

This is more than true concerning singer-songwriter-guitarist Iain David McGeachy, better known as John Martyn (1948-2009).

He underwent a quite eclectic musical upbringing. In the mid 1960s his interests turned to folk and blues,

fascinated by Joan Baez's fast finger-picking. John took lessons with iconic folk singer Hamish Imlach and

learned the rudiments of a bluesy acoustic guitar style. From Imlach he also learned the troubadour's code: you travelled, you played, you drank, you met women.

John began writing songs before he had even fully mastered his instrument. He also tested out different tunings, favouring DADDAD, dropped D, and open C.

As a consequence,

Martyn played his songs in the same order each time, because he didn't know how he had got from one tuning to the other, in terms of the theory of it. Instead,

he simply memorised the entire routine.

His professional musical career began when he was just seventeen, playing a blend of blues and folk music. It resulted in a unique style that made

him a key figure in the London folk scene. At the same time, guitarists such as Davy Graham and Bert Jansch became lodestars for him:

their desire to pull away from folk into more exotic territories proved inspirational to his developing tastes.

More personally, he married Maureen Beverley Kutner, a folk/pop singer who had played the Monterey Pop festival. They made two albums together,

a success for John, more or less the end of Beverley's musical career.[63]

It wasn't a happy marriage anyway.

It was a passionate, deeply felt love affair. It was also a catastrophically ill-matched union, one which cruelly curtailed Kutner's career and

ultimately wrought an immense amount of damage and destruction.

John Martyn lives his music. He developed a wholly original and peculiar sound: a one-man band armed only with guitar and an

electronic effects box of amplification, echoing, reverbs and loops. He was reluctant of putting a straight rock beat over traditional music,

but favoured polyrhythms and modal music. Besides he developed a slurred vocal style, resembling something like a tenor saxophone.

Thus, pushing the borders of guitar playing and singing, he outgrew the British folk circuit of the time. He was determind to

reach the stars, so it seemed, wasn't it for his unreliability tripping him up every now and then.

His life settled into the reliable rhythms of dysfunctional relationships, functioning alcoholism, relentless touring, recreational drugging,

punctuated by wild, frightening binges which brought out the worst of him.

[...] Heavily bearded, with his receding hair slicked back, wearing suits, sunglasses and Crombie coats, he could have passed for a middle-ranking

crime boss come to collect his protection money.

In 2003, John Martyn's right leg had to be amputated below the knee. He died in 2009 due to acute respiratory distress,

affected by his life-long abuse of drugs and alcohol.

Nobody will remember me when I'm gone, he once had quipped. His death didn't make the headlines indeed,

but the first tribute album didn't come much after, homage paid by

David Gilmour, Phil Collins, Beck, Snow Patrol, Beth Orton,Joe Bonamassa, amongst others.

On the tenth anniversary of his death, a tribute concert was held at the Royal Concert hall in Glasgow as part of Celtic Connections,

featuring the likes of Danny Thompson, John Smith, Blue Rose Code, Eddi Reader and Eric Bibb.

Graeme Thomson, author of fine books about the life and music of Johnny Cash[45]

and Kate Bush,[49]

manages to give a true account, warts-and-all, of a complex and not always likeable individual,

who nevertheless must be praised for his artistic merits.

P.S.: "Graeme asked myself and a few songwriters who were inspired by John Martyn to record versions of his songs as part of the promotional campaign for the book.

You can find them all at Folk Radio UK.

Olivia Chaney, Karine Polwart, Blue Rose Code, Siobhan Wilson and I covered May You Never, Over the Hill,

Couldn't Love You More, Fine Lines and Spencer the Rover." - Findlay Napier

An album that frequently cuts loose from the moorings of conventional songwriting drops a significant clue regarding its intentions in the opening seconds. Martyn comments that whichever sounds the musicians had been creating prior to the listener’s arrival had felt ‘natural’, before sliding sleepily into the opening track: Fine Lines. From the start, we are alerted to the fact that what we’re hearing is merely an excerpt, edited highlights of a larger whole.

Inside Out is often guided by surf and stars rather than map and compass, yet there are wonderful songs, too. Fine Lines is one of Martyn’s very best, as tender a song of friendship as May You Never, except that here the love extends beyond a brother to a brotherhood of the ‘finest folk in town’. It reeks of woozy late-night gatherings, the 5 a.m. pre-dawn reckoning when the music settles to a faint pulse, the bright edge of the chemicals begin to soften and blur the senses, and the awareness of a universal human bond is a matter of peaceful certitude.

Fine Lines cuts deeper than the drunken arm slung around the shoulder, travelling through skin and bone to the soul, via the deeply felt connections forged in smoke-filled rooms and over smeared glasses, in the warm communion of bodies slumped platonically on sofas. Loneliness is there, too, whispering at the window, the exquisite sadness that comes from knowing that good times are ending even as they are happening. The fragility is so profound one can hear the air shake around the strings, feel the cadences of all those empty spaces.

On an album where the tapping of folk sources was more overt than usual, the highlight is Spencer The Rover, a venerable traditional song with its provenance in East Sussex and Yorkshire, and which Martyn learned from one of the latter county’s many fine folk singers, Robin Dransfield. Martyn was particularly enamoured with it. The following spring, the song gave its name to his second child, christened Spenser Thomas McGeachy.

‘He initially asked me to sing on Spencer The Rover,’ says Martin Carthy. ‘Nothing came of it, in the end. Don’t know why. It tells you a lot about him that he loved that song so much. It spoke to him. It’s a very grown-up song. I never understood it when I was twenty; when I was forty I did. The results were very true to the song, but very John.’

He sang it with rapturous tenderness on Sunday’s Child, and many times more on stage in the years thereafter. Though he did not write the words, in his hands they read like wishful autobiography. In its empathetic depiction of a man who has been ‘much reduced’ and ‘caused great confusion’, one can hear a romanticised echo of Martyn’s own transgressive wanderings.

In the song, Spencer has abandoned his family and embarked on a troubled, aimless ramble around the countryside. In Yorkshire, he beds down for the night in a forest. After a restless sleep, punctuated by dream-sent voices imploring him to go home, he returns to the family fold, a near-stranger welcomed lovingly back into their arms. Spencer is thereafter resolved to a future filled with nothing more taxing than taking his children upon his knee and listening to their ‘prittle-prattling stories’. It is a song about setting aside youthful appetites and wild schemes to instead settle for the simplest and most enriching rewards.

For Martyn, such home comforts were fleeting and rare. Though they were similarly cherished, at least in theory, they offered only temporary respite. The song smooths out the edges of his cavalier ways. Perhaps that’s why he cradles it like precious cargo. It offers a glimpse of another path, impossible to follow but close enough to touch. He could never have written the words, but he sings them as sacred text. The performance is so powerful partly because it offers the happy ending his own actions denied him.

One World synthesised the old and new, marrying Martyn’s traditional heart and soul to a sinewy energy and fresh, luxuriant textures. Punk had broken through during the period in which the album was written and recorded, but it made little impact on him. He claimed to enjoy the Sex Pistols, and for at least one member of the band the feeling was mutual: John Lydon was a Martyn fan, spotted at several shows. But, for a man beholden to slow music, the abrasion of punk was never going to be his thing, even if he rather admired the attitude.

The album was less personal in some ways, certainly less intimate, than Martyn’s recent records. Couldn’t Love You More was the one direct connection to his former work, a simple acoustic performance featuring Danny Thompson’s sawing bass undertow and dappled sprinkles of vibes. The lyric was one of his most tender, if ambiguous, declarations. ‘On a simple level it’s saying, “I gave you everything,”’ says Ralph McTell. ‘On another level, it says, “I didn’t have any more that I could pull out to give you.” He had a light touch, but there was a terrible, awe-inspiring darkness in him as well. He was one of those artists who could articulate what we suspect is this darkness we feel in ourselves. Sometimes we don’t want to see it.’

The unease which runs through Over The Hill belies the breezy hop and skip in the music, with its twinkly conjuring of caravans and campfires. It is a song of conflict, between the open road and the four walls of hearth and home. The title phrase, of course, can also refer to someone who is past their best. The journey Martyn describes is a homecoming – the run into Hastings on the train rolled through rising countryside before the line dipped down to reveal the town – but also a more ambiguous internal one.

Martyn often spoke about domesticity equating the death of creativity. He was a subscriber to the Cyril Connolly school of cliché that the pram in the hallway is the solemn enemy of good art, yet he also yearned for his family, its wholesome comforts and simple certainties. In Over The Hill, he is worried about ‘my babies’ and ‘my wife’; worried, too, about what they are doing to him, and he to them.

‘You could put it into a hymn book,’ says Richard Thompson of Martyn’s best-known and popular composition. ‘It’s a beautiful song.’ The most common thesis is that he wrote May You Never for his friend Andy Matthews, who ran the Soho cellar club, Les Cousins. Then again, Scottish writer and folk singer Ewan McVicar has met ‘three people who told me who that song was written about. All different.’ Others theorise that it was written about Martyn’s own children. Paul Wheeler refutes the idea that it is about, or for, any person in particular. ‘As I remember, he wrote it very much as a signature song. It was a very calculated thing.’ Wheeler recollects that the line about love being a lesson ‘we learn in our time’ was loosely appropriated from Lesley Duncan’s Love Song.

Such utility is the great value of May You Never. It feels usable, relatable. We all know someone about whom it could or should have been written. It is a series of very secular prayers for a wayward sibling-cum-soulmate to keep his woman close, his temper in check, and to always have a warm place to lay his head. That these pitfalls were all directly pertinent to Martyn’s personal hang-ups and weaknesses lends weight to the interpretation that he was, at least partly, singing to himself. Though it remains his most famous song, covered by superstars and bar-stool amateurs alike, he never quite saw what the fuss was about, and at times resented the dominance it came to demand in his catalogue. When I raised this with him, he shrugged and called it a ‘lollipop’, a sweet, simple and insubstantial diversion.

Terra Incognita Tuva: A journey among Nomads, Shamans and Musicians.

JARO Medien, Past & Present Series, 2020,

ISBN 978- 3-9813509-6-8, 146 S, €35,00 (incl. CD & DVD)

Terra Incognita Tuva: A journey among Nomads, Shamans and Musicians.

JARO Medien, Past & Present Series, 2020,

ISBN 978- 3-9813509-6-8, 146 S, €35,00 (incl. CD & DVD) Now we undertake a geographic leap into the remote steppe of Central Asia. Tuva is an autonomous republic belonging to the Russian Federation in the southern part of Siberia, located on the north-western border of Mongolia. Tuva is a largely unknown country - except perhaps as the home of larynx and overtone singing, especially the internationally touring ensemble Huun-Huur-Tu.

After 25 years of working with Huun-Huur-Tu, Jaro head Ulrich Balss travelled to Terra Incognita Tuva. The result is - after

Lisbon[60]

and New York[67][70]

- the 3rd photo book from the "Past & Present" series, another total work of art consisting of photos and interviews, history and stories, facts and myths. And of course music, but about that in a moment.

Perhaps a few clichés beforehand: We know the treasures of the ancient Scythians discovered a few years ago, as well as the nomadic horse people that fought for Genghis Khan a millennium and a half later. In fact, Huun-Huur-Tu sing about horses in many songs, but beyond the paddock and yurt you can discover the resurgent shamanism, the national sport of wrestling and the curious triangular stamps issued during the short period of political independence.

Ethnically speaking, today's Tuvinians are Turkish people who immigrated from Anatolia in the 9th century. Or vice versa, German and English text are not always identical. So it's not clear to me whether the monument that marks the center of Asia is now near or in the middle of the capital Kyzyl.

The focus of the book, however, is the family history of Radik Tyulyush, one of the musicians from Huun-Huur-Tu, which Ulrich Balss traces back to the beginning of the 20th century. He has the following to say about Radik Tyulyush:

At his birth [1974], the doctor remarked what a loud and melodic voice Radik had ...

He always spent his summer holidays at the grandparents' place and enjoyed the nomadic life.

His grandparents taught him the traditional songs and he began to sing on his own in the wild, and began to develop a great respect for his environment.

... At the [age] of 14, he began to write songs and lyrics and founded the rock group Üjer, in 1994 ...

His greatest wish was to study at the Alexei Boktaevich Chirgal-ool Music College (named after a famous Tuvan composer). The course of study was

National Musical Instruments which also offered training in singing.

... In 2000, Albert Kuzevin invited him to join the well-known band Yat-Kha.

... In 2006 he joined Huun-Huur-Tu and has remained a permanent ensemble member until today.

The book is supplemented by a live recording of Huun-Huur-Tu from last year as well as a German TV production from 1996 about overtone singing and nomad culture, entitled

"Secrets of Chöömei" - the term Chöömei is sometimes used as a generic term, sometimes used as a special style. Music producer and journalist

Wolfgang Hamm travelled to Tuva in August 1996:

At the end of my first trip to Tuva, Sasha Bapa made me a cassette of his four-man group, and it became crystal clear to me that Huun-Huur-Tu were

on their way to transform the basically solo art of chöömei into an ensemble art form. The singing is accentuated by percussion instruments such as the

shaman's drum, small bells, rattles made of bulls scrotums, filled with sheeps knuckles, and a clapper made from horse hooves all join up with vocal

solos in various styles of chöömei. The finale consists of a piece which lifts the entire concert to an exuberant tonal climax. Here, the deep Kargyraa

and the high, whistling Sygyt styles are finely accompanied by the cello-like horse-head fiddle Igil, the long-necked lutes Toshpulur and Tschansy, as

well as the flageolet technique of the bowed Bysaanchy. The sounds of the jaw-harp Chomus, the hunting horn Amyrga made from birch bark, and a

mysterious-sounding bull-roarer, spun in circles to imitate the wind, create suspense and colour. Huun-Huur-Tu, a name which recalls the vertical

separation of light beams on the steppe just after dawn and just before sunset - with their very diverse repertoire, we repeatedly encounter similar

motifs from the nomads' world: The love of Nature, for father, mother and next of kin, the love for trustworthy animalsespecially the horse, which plays

such a central role in Tuvan culture. There is also the yearning after a long journey, to be once again at home with the beloved...

In view of the fact that there is no comprehensive book on the subject of Tuva and that travelling is currently out of the question anyway, I am pleased about this colorful splash of color on a white spot of our mental map.

Huun-Huur-Tu should have presented the book in autumn, the shows have been postponed to 2021. A visit can only be recommended and the closing words are left to Radik Tyulyush:

Sing. With your singing your soul becomes kinder. And if a person sings, then he feels harmony. Become better and kinder with the music. Our world needs our kindness.

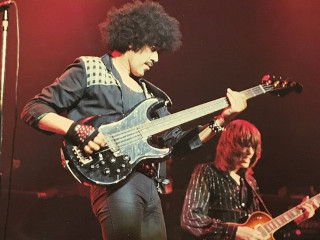

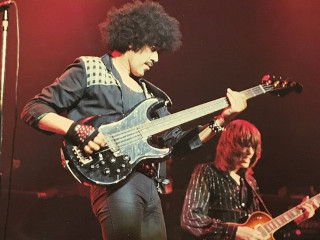

Graeme Stroud, on track ... Thin Lizzy... Every Album, Every Song.

Sonicbond Publishing,

2020, ISBN 978‐1‐78952‐064‐4, pp128, €17,99

Graeme Stroud, on track ... Thin Lizzy... Every Album, Every Song.

Sonicbond Publishing,

2020, ISBN 978‐1‐78952‐064‐4, pp128, €17,99

With its back against the wall of the Atlantic Ocean and its face towards Britain

and the vast sweep of the Eurasian continent beyond, Ireland is an outsider,

the last outpost of Western Europe. Steeped in the musical tradition of Gaelic

folk, Ireland has nevertheless contributed some stellar characters to the history

of rock, in which the name of Thin Lizzy looms large. And when discussing the

rock band Thin Lizzy, it is no mistake to concentrate heavily on its instigator,

lyricist and public-facing persona, the late Philip Lynott.

Black and Irish like a pint of Guinness, as he famously quipped, Phil Lynott's way with words and

his on-stage persona made Thin Lizzy one of the most iconic rock bands of the 1970s in Europe. The band's

debut album was released in 1971:

It is more progfolk than rock... This set is quiet and introspective, even cerebral, and shows

Lynott not as a rocker, not even as a songwriter per se, but purely and simply

as a poet. True, that was the way of contemporary Irish music in the ‘60s and

early ‘70s, and it is easy to imagine some of these songs being crooned by Van Morrison.

One of the most memorable tracks has been called "Eire":

Lynott sings a poem concerning Celts versus Vikings set to a gorgeously

ambient but surprisingly complex backing of acoustic and reverb-soaked

electric guitars, tom rolls and melodic bass runs... Lynott was keen to sing

the lyrics in Irish Gaelic, and reportedly recorded a take in that language, but

that was a step too far for Decca and he re-did it in English.

Their breakthrough in the charts was their take on the traditional Irish folk song, "Whisky In The Jar,"

released as a single in November 1972. Lynott said,

‘After the success of “Whisky in the Jar” there was an awful lot of pressure on the band. People wanted us to record ‘Tipperary’ rocked up, or “Danny Boy” rocked up.’

The song wasn't even put on the forthcoming album. The "Jailbreak" and the song "The Boys Are Back In Town" became a lecture in power-rock, and

it turned the boys into rock stars.

Thin Lizzy... Every Album, Every Song presents a history of the band through its musical releases,

everything from melodic rock to soul, prog, folk, fusion and romantic balladry. Along the way it

follows a series of terrific lead guitarists. At the end of the 1970s, Thin Lizzy featured one Gary Moore, who

was receptive to the Irish folk influences and Gaelic melodic phrasing.

These influences reached their peak with Moore in the the track "Róisín Dubh (Black Rose): A Rock Legend" from 1979:

The first minute and three quarters are entirely original, a melodic and uplifting

piece with a generally Gaelic feel. First it introduces us to the legend of Cú Chulainn, ...

There is some glorious, frenetic fast drumming in a slightly odd time

signature – it alternates between bars in 3/4 and 4/4 time, so it seems to skip a

beat every couple of bars – and an absolute guitarfest as the axes harmonise,

then call and answer, then harmonise again. ... The lyrics branch off into a reference to ‘The Mountains Of Mourne,’ a

song by Irishman Percy French at the close of the nineteenth century. At 1:45

we are treated to an abrupt change, as the guitar starts to pick out the tune

to ‘Shenendoah’, which is actually a traditional American song, but fits the

mood of the piece perfectly. Lynott extemporises the vocals to some extent,

and it morphs imperceptibly into the Scottish-Irish ballad ‘Wild Mountain

Thyme’ (otherwise known as ‘Will Ye Go Lassie Go’) ... At 2:10 we hear a few bars of an

instrumental rendition of the traditional Irish ‘Danny Boy’ (or ‘Londonderry

Air’ – it’s the same tune). From 2:33 the guys riff on these and similar chord

progressions, changing again from 3:18 to a traditional-style Irish jig or reel.

The tune is rolling like a river, washing joyously over the listener until 4:04

when everything stops and Moore goes into his showpiece – a manically fast

interpretation of ‘The Mason’s Apron’, a reel with Moore playing both the

calling and answering guitars.

Everything stops at the five-minute mark and Lynott sings a slow section with

a mandolin-style guitar and synthy keyboard-washed backing, then everything

goes into the outro – Lynott puts in as many Irish-related references as he can:

Róisín Dubh, novelist James Joyce, poet William Butler Yeats, playwright Oscar

Wilde, writer Brendan Behan, 1964 movie Girl With Green Eyes (adapted by

Irish novelist Edna O’Brien from her book The Lonely Girl), Dark Rosaleen,

(another incarnation of Róisín Dubh), footballer George Best, singer Van

Morrison, a glancing reference to the Irish potato famine of the 19th century,

Thin Lizzy’s own traditional hit ‘Whisky In The Jar’, John Synge’s play The

Playboy Of The Western World, The Mountains of Mourne in Northern Ireland

and music hall singalong ‘It’s A Long Way To Tipperary’. He’s still adding to the

list as the song eventually fades out, over seven minutes after it started.

Phil Lynott died on 4 January 1986, effectively as a result of a persistent heroin addiction. He was 36.

‘Whisky In The Jar’ (Traditional arr. Lynott, Bell, Downey, full length version 5:45)

Released as a cut-down 3:43 single on 3 November 1972, intended as the

B-side to ‘Black Boys On The Corner’ but then promoted to be the A-side

before release, this was the song that gave Thin Lizzy their first taste of chart

success. This single is almost worth a chapter of its own; it gave the band the

leg-up they required and effectively saved their careers (for the first time) and

their sanity. The story behind it is not a short one either.

Firstly though, a word about the spelling: Scotch distillers invariably describe

their wares as ‘whisky’, without an ‘e’. Most Irish and American brands are

labelled as ‘whiskey’ with an ‘e’. When referred to in print, the name of this

single is almost inevitably spelt with an ‘e’, which would be the correct spelling

– however, neither on the original single nor on any subsequent canonical release, did it ever contain the ‘e’.

After Lizzy’s first two albums bombed, they were starting to lose heart and

their record label to lose faith. In line with the mind-set of the day’s serious

musicians, Thin Lizzy were never about hits or singles; they were a much

more album-oriented proposition; in any case, their whimsical, poetry-based,

musically complex approach was never likely to churn out the hits like Buddy

Holly’s simple songs or The Monkees’ jolly ditties. Nevertheless, to a record

label, a band is just a tool for printing money, and Thin Lizzy needed to come

up with a hit single. ‘Whisky In The Jar’ was never meant to be that single; it

is a traditional Irish folk song and the boys started playing it at a jam session

one night when they couldn’t find inspiration anywhere else. It was their comanager

Ted Carroll who spotted the song’s potential in the trio’s hands, but

clearly, they were trying to come up with something original and wouldn’t

consider recording the old ballad.

Anyway, Lynott reckoned his new song ‘Black Boys On The Corner’ was

good enough to make the grade; a gritty, funky piece of rock soul, it got the

nod from the label. All 45s need a B-side though, and Carroll was keen to

promote ‘Whisky In The Jar’, which played up their Celtic roots nicely, so they

reluctantly agreed to hammer out a version.

Clearly, they needed to rock it up a bit, but it reportedly took Eric Bell a

fortnight of mucking about, jamming along with a tape copy, before he came

up with the now-iconic electric guitar riff that makes Lizzy’s version so instantly

recognisable. Interestingly, Lynott and Bell both strum acoustic guitars on this

one; Eric Bell said they couldn’t afford to hire an extra musician, but it never

seems to have occurred to them to dub on a bass afterwards, even though they

dubbed on the lead guitar – so this song contains no bass guitar.

The single was recorded, pressed and released behind schedule, but despite

all the sweat that had gone into it, it too dropped like a stone – at first. Decca

had insisted that ‘Whisky’ would be the featured song out of the two, so it was

promoted to the A-side, and some bright spark had the idea of shipping out

miniature bottles of whisky to all the DJs and record stations along with copies

of the single.

Meanwhile, a demoralised Lizzy were going through the motions on a

German tour. Down and depressed, drinking heavily, Lynott and Bell ended up

slugging it out in a hotel one night and Downey threatened to pack the whole

game in. Then suddenly, they had word from head office that ‘Whisky’ had hit

the charts and was currently residing at no. 25. The tour was a disaster anyway,

so they cancelled the rest and high-tailed it back home to promote the single,

which eventually climbed to no. 6 in the UK, a massive no. 1 in Ireland, and

ironically it ended up getting to no. 10 in Germany too. Amid massive backslapping

and relief all round, it gave Thin Lizzy their first appearance on Top Of

The Pops and new kudos with Decca. The big time called.

A word about the song itself: It was based on notorious Irish highwayman

Patrick Fleming. Not one of Ireland’s finest, he murdered, robbed and

maimed indiscriminately, men, women, children, rich and poor alike, and

was eventually hunted down and captured. Fleming famously escaped at

one point by scrambling up a chimney but was eventually recaptured and

was hanged in 1650. It was common for such ‘gentlemen of the road’ to

take on a heroic air in their local district, but in Scotland and Ireland, where

they tended to target rich English landlords, they tended to be regarded as

national patriots. ‘Whisky’ was written about the time of Cromwell’s invasion

of Ireland, when England’s repute in Ireland was rock bottom and even

a miscreant like Fleming was viewed through rose-coloured glasses. The

song was also transferred to America with the Irish emigrants and adapted

into various patriotic forms during the Civil War, especially amongst Irish

battalions.

If you’ve ever wondered what that ‘Musha ring dumma do dumma da’ bit

is all about, with its ‘whack for ma daddy-o,’ the answer is that no-one really

knows, as Brian Downey explained to the author:

Whoever wrote it originally stuck a Gaelic phrase in there, but over the

years, the Gaelic was lost and the English was substituted. I mean the song

is pretty ancient; ‘Highwayman songs’ they used to be called. And it was

mispronounced over all those years, so it comes out as ‘musha ring dumma do

dumma da’, then it’s actually ‘whack fol, (with an L), de-daddy-o.’

In any case, after Thin Lizzy went on to success with the Vertigo label, Decca

trotted this one out from time to time. The full-length version was released

on 27 Jan 1978, with two later songs, ‘Vagabonds Of The Western World’ and

‘Sìtamoia’ on the B-side. It was then released in 1979 and again in 1983 with

‘The Rocker’ on the B-side. The single appeared on the Decca compilation

Remembering Part 1 in 1976 and both versions were included on the 2010

expanded 2-CD edition of the album Vagabonds Of The Western World.

Photo Credits:

(1ff) Book/CD Covers,

(8) John Martyn,

(9) Scott Cook,

(10) Chris Regez,

(11) Olivia Chaney,

(12) Findlay Napier,

(13)-(14) Huun-Huur-Tu (Radik Tyulyush),

(15) (Thin Lizzy)

(from website/author/publishers).

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld