As down the glen one Easter morn... The 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin spawned a couple of Songs That Made History. While the Easter Rising's 100th anniversary is celebrated in 2016, one can expect that many of them are voiced throughout Ireland.

The Easter Rising (Irish: Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week, 1916. The Rising was mounted by Irish republicans to end British rule in Ireland and establish an independent Irish Republic while the United Kingdom was heavily engaged in World War I. It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798.

The Foggy Dew As down the glen one Easter morn to a city fair rode I There Armed lines of marching men in squadrons passed me by No fife did hum nor battle drum did sound it's dread tattoo But the Angelus bell o'er the Liffey swell rang out through the foggy dew Right proudly high over Dublin Town they hung out the flag of war 'Twas better to die 'neath an Irish sky than at Sulva or Sud El Bar And from the plains of Royal Meath strong men came hurrying through While Britannia's Huns, with their long range guns sailed in through the foggy dew 'Twas Britannia bade our Wild Geese go that small nations might be free But their lonely graves are by Suvla's waves or the shore of the Great North Sea Oh, had they died by Pearse's side or fought with Cathal Brugha Their names we will keep where the fenians sleep 'neath the shroud of the foggy dew But the bravest fell, and the requiem bell rang mournfully and clear For those who died that Eastertide in the springing of the year And the world did gaze, in deep amaze, at those fearless men, but few Who bore the fight that freedom's light might shine through the foggy dew Ah, back through the glen I rode again and my heart with grief was sore For I parted then with valiant men whom I never shall see more But to and fro in my dreams I go and I'd kneel and pray for you, For slavery fled, O glorious dead, When you fell in the foggy dew.Listen to The Foggy Dew from: Ron Kavana, Tomas Lynch, Norland Wind, The Pints, Brian Roebuck, Runa

Watch The Foggy Dew from: Banshee, The Dubliners, Gráinne Holland, Luke Kelly, Sinead O'Connor, The Wolfe Tones

Organised by seven members of the Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Rising began on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, and lasted for six days. Members of the Irish Volunteers — led by schoolmaster and Irish language activist Patrick Pearse, joined by the smaller Irish Citizen Army of James Connolly, along with 200 members of Cumann na mBan — seized key locations in Dublin and proclaimed an Irish Republic. There were isolated actions in other parts of Ireland, with an attack on the Royal Irish Constabulary barracks at Ashbourne, County Meath and abortive attacks on other barracks in County Galway and at Enniscorthy, County Wexford.

With vastly superior numbers and artillery, the British army quickly suppressed the Rising, and Pearse agreed to an unconditional surrender on Saturday 29 April. Most of the leaders were executed following courts-martial, but the Rising succeeded in bringing physical force republicanism back to the forefront of Irish politics. Support for republicanism continued to rise in Ireland. In December 1918, republicans (by then represented by the Sinn Féin party) won 73 Irish seats out of 105 in the 1918 General Election to the British Parliament, on a policy of abstentionism and Irish independence. On 21 January 1919 they convened the First Dáil and declared the independence of the Irish Republic, and later that same day the Irish War of Independence began with the Soloheadbeg ambush.

The Acts of Union 1800 united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, abolishing the Irish Parliament and giving Ireland representation at Westminster. From early on, many Irish nationalists opposed the union as the ensuing exploitation and impoverishment of the island led to a high level of depopulation.

Opposition took various forms: constitutional (the Repeal Association; the Home Rule League), social (disestablishment of the Church of Ireland; the Land League) and revolutionary (Rebellion of 1848; Fenian Rising). Constitutional nationalism seemed to be about to bear fruit when the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) under Charles Stewart Parnell succeeded in having the First Home Rule Bill of 1886 introduced by the Liberal government of William Ewart Gladstone, but it was defeated in the House of Commons. The Second Home Rule Bill of 1893 was passed by the Commons but rejected by the House of Lords.

After the fall of Parnell, younger and more radical nationalists became disillusioned with parliamentary politics and turned toward more extreme forms of separatism. The Gaelic Athletic Association, the Gaelic League and the cultural revival under W. B. Yeats and Lady Augusta Gregory, together with the new political thinking of Arthur Griffith expressed in his newspaper Sinn Féin and organisations such as the National Council and the Sinn Féin League led to the identification of many Irish people with the concept of a Gaelic nation and culture, completely independent of Britain. This was sometimes referred to by the generic term Sinn Féin, particularly by the authorities.

The Third Home Rule Bill was introduced by British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith in 1912, beginning the Home Rule Crisis. The Irish Unionists, led by Sir Edward Carson, opposed Home Rule under what they saw as an impending Roman Catholic-dominated Dublin government. They formed the Ulster Volunteer Force on 13 January 1913, creating the first paramilitary group of 20th century Ireland.

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) saw an opportunity to create an armed organisation to advance its own ends, and on 25 November 1913 the Irish Volunteers, whose stated object was "to secure and to maintain the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland", was formed. Its leader was Eoin MacNeill, who was not an IRB member. A Provisional Committee was formed that included people with a wide range of political views, and the Volunteers' ranks were open to "all able-bodied Irishmen without distinction of creed, politics or social group." Another militant group, the Irish Citizen Army, was formed by trade unionists as a result of the Dublin Lock-out of that year. The increasing militarisation of Irish politics was overshadowed soon after by the outbreak of the First World War and Ireland's involvement in the conflict.

Though many Irishmen had volunteered for Irish regiments and divisions of the New British Army at the outbreak of war in 1914, the growing likelihood of enforced conscription created a backlash. Opposition to the war was based particularly on the implementation of the Government of Ireland Act 1914 (as previously recommended in March by the Irish Convention) increasingly and controversially linked with a "dual policy" enactment of the Military Service Bill, a dual policy that would require Irish conscription to begin if there would be any hope of Ireland seeing the implementation of the Government of Ireland Act 1914. The linking of conscription and Home Rule outraged the Irish secessionist parties at Westminster, including the IPP, the All-for-Ireland League and others, who walked out in protest and returned to Ireland to organise opposition.

Off to Dublin in the Green And we're all off to Dublin in the green, in the green Where the helmets glisten in the sun Where the bayonets flash and the rifles crash To the rattle of a Thompson gun Oh I am a merry ploughboy and I ploughed the fields all day Till a sudden thought came to my head that I should roam away For I'm sick and tired of slavery since the day that I was born And I'm off to join the IRA, and I'm off tomorrow morn I'll leave aside my pick and spade, I'll leave aside my plough I'll leave aside my horse and yoke, I no longer need them now And I'll leave aside my Mary, she's the girl that I adore And I wonder if she'll think of me when she hears the rifles roar And when the war is over and dear old Ireland is free I'll take her to the church to wed, and a rebel's wife she'll be Well, some men fight for silver and some men fight for gold But the IRA are fighting for the land that the Saxons stoleWatch Off to Dublin in the Green from: Father Michael Cleary, The Dubliners, Flipper Flannigan's Flat Footed Four

The Supreme Council of the IRB met on 5 September 1914, just over a month after the UK government had declared war on Germany. At this meeting, they decided to stage a rising before the war ended and to accept whatever help Germany might offer. Responsibility for the planning of the rising was given to Tom Clarke and Seán MacDermott. The Irish Volunteers—the smaller of the two forces resulting from the September 1914 split over support for the British war effort—set up a "headquarters staff" that included Patrick Pearse as Director of Military Organisation, Joseph Plunkett as Director of Military Operations and Thomas MacDonagh as Director of Training. Éamonn Ceannt was later added as Director of Communications.

In May 1915, Clarke and MacDermott established a Military Committee within the IRB, consisting of Pearse, Plunkett and Ceannt, to draw up plans for a rising. This dual rôle allowed the Committee, to which Clarke and MacDermott added themselves shortly afterward, to promote their own policies and personnel independently of both the Volunteer Executive and the IRB Executive—in particular Volunteer Chief of Staff Eoin MacNeill, who supported a rising only on condition of an increase in popular support following unpopular moves by the London government, such as the introduction of conscription or an attempt to suppress the Volunteers or its leaders, and IRB President Denis McCullough, who held similar views. IRB members held officer rank in the Volunteers throughout the country and took their orders from the Military Committee, not from MacNeill.

Plunkett travelled to Germany in April 1915 to join Roger Casement, who had gone there from the United States the previous year with the support of Clan na Gael leader John Devoy, and after discussions with the German Ambassador in Washington, Count von Bernstorff, to try to recruit an "Irish Brigade" from among Irish prisoners of war and secure German support for Irish independence. Together, Plunkett and Casement presented a plan which involved a German expeditionary force landing on the west coast of Ireland, while a rising in Dublin diverted the British forces so that the Germans, with the help of local Volunteers, could secure the line of the River Shannon.

James Connolly—head of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), a group of armed socialist trade union men and women—was unaware of the IRB's plans, and threatened to start a rebellion on his own if other parties failed to act. If they had gone it alone, the IRB and the Volunteers would possibly have come to their aid; however, the IRB leaders met with Connolly in January 1916 and convinced him to join forces with them. They agreed to act together the following Easter and made Connolly the sixth member of the Military Committee. Thomas MacDonagh would later become the seventh and final member.

In an effort to thwart both informers and the Volunteers' own leadership, Pearse issued orders in early April for three days of "parades and manoeuvres" by the Volunteers for Easter Sunday (which he had the authority to do, as Director of Organisation). The idea was that the republicans within the organisation (particularly IRB members) would know exactly what this meant, while men such as MacNeill and the British authorities in Dublin Castle would take it at face value. However, MacNeill got wind of what was afoot and threatened to "do everything possible short of phoning Dublin Castle" to prevent the rising.

MacNeill was briefly convinced to go along with some sort of action when Mac Diarmada revealed to him that a shipment of German arms was about to land in County Kerry, planned by the IRB in conjunction with Roger Casement; he was certain that the authorities' discovery of such a shipment would inevitably lead to suppression of the Volunteers, thus the Volunteers were justified in taking defensive action, including the originally planned manoeuvres. Casement—disappointed with the level of support offered by the Germans— insisted on returning to Ireland on a German U-boat and was captured upon landing at Banna Strand in Tralee Bay. His reason for travel was to stop or at least postpone the Rising. The arms shipment was lost when the German ship carrying it, Aud, was scuttled after interception by the Royal Navy. The ship had already attempted a landing, but the local Volunteers failed to rendezvous at the agreed time.

The Dying Rebel The night was dark, and the fight was over, The moon shone down O'Connell Street, I stood alone, where brave men perished Those men have gone, their God to meet. My only son was shot in Dublin, Fighting for his country bold, He fought for Ireland, and Ireland only, The Harp and Shamrock, Green, White and Gold. The first I met was a grey-haired father Searching for his only son, I said "Old man, there's no use searching For up to heaven, your son has gone". The old man cried out broken hearted Bending o'er I heard him say: "I knew my son was too kind hearted, I knew my son would never yield". The last I met was a dying rebel, Bending low I heard him say: "God bless my home in dear Cork City, God bless the cause for which I die."Watch The Dying Rebel from: Derek Warfield, Patsy Watchorn

The following day, MacNeill reverted to his original position when he found out that the ship carrying the arms had been scuttled. With the support of other leaders of like mind, notably Bulmer Hobson and The O'Rahilly, he issued a countermand to all Volunteers, cancelling all actions for Sunday. This succeeded in putting the rising off for only a day, although it greatly reduced the number of Volunteers who turned out.

British Naval Intelligence had been aware of the arms shipment, Casement's return, and the Easter date for the rising through radio messages between Germany and its embassy in the United States that were intercepted by the Navy and deciphered in Room 40 of the Admiralty. The information was passed to the Under-Secretary for Ireland, Sir Matthew Nathan, on 17 April, but without revealing its source, and Nathan was doubtful about its accuracy. When news reached Dublin of the capture of the Aud and the arrest of Casement, Nathan conferred with the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Wimborne. Nathan proposed to raid Liberty Hall, headquarters of the Citizen Army, and Volunteer properties at Father Matthew Park and at Kimmage, but Wimborne insisted on wholesale arrests of the leaders. It was decided to postpone action until after Easter Monday, and in the meantime Nathan telegraphed the Chief Secretary, Augustine Birrell, in London seeking his approval. By the time Birrell cabled his reply authorising the action, at noon on Monday 24 April 1916, the Rising had already begun.

Early on Monday morning, 24 April 1916, roughly 1,200 Volunteers and Citizen Army members took over strongpoints in Dublin city centre. A joint force of about 400 Volunteers and Citizen Army gathered at Liberty Hall under the command of Commandant James Connolly.

The rebel headquarters was the General Post Office (GPO) where James Connolly, overall military commander and four other members of the Military Council: Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke, Seán Mac Dermott and Joseph Plunkett were. After occupying the Post Office, the Volunteers hoisted two Republican flags and Pearse read a Proclamation of the Republic.

Elsewhere, rebel forces took up positions at the Four Courts, the centre of the Irish legal establishment, at Jacob's Biscuit Factory, Boland's Mill, the South Dublin Union hospital complex and the adjoining Distillery at Marrowbone Lane. Another contingent, under Michal Mallin, dug in on St. Stephen's Green.

Although it was lightly guarded, Volunteer and Citizen Army forces under Seán Connolly failed to take Dublin Castle, the centre of British rule in Ireland, shooting dead a police sentry and overpowering the soldiers in the guardroom, but failing to press home the attack. The Under-secretary, Sir Matthew Nathan, alerted by the shots, helped close the castle gates. The rebels occupied the Dublin City Hall and adjacent buildings. They also failed to take Trinity College, in the heart of the city centre and defended by only a handful of armed unionist students. At midday a small team of Volunteers and Fianna Éireann members attacked the Magazine Fort in the Phoenix Park and disarmed the guards, with the intent to seize weapons and blow up the building as a signal that the rising had begun. They set explosives but failed to obtain any arms.

In at least two incidents, at Jacob's and Stephen's Green, the Volunteers and Citizen Army shot dead civilians trying to attack them or dismantle their barricades. Elsewhere, they hit civilians with their rifle butts to drive them off.

The British military were caught totally unprepared by the rebellion and their response of the first day was generally un-coordinated. Two troops of British cavalry, one at the Four Courts and the other on O'Connell Street, sent to investigate what was happening took fire and casualties from rebel forces. On Mount Street, a group of Volunteer Training Corps men stumbled upon the rebel position and four were killed before they reached Beggars Bush barracks.

James Connolly (I) Where oh where is our James Connolly? Where oh where is that gallant man? He's gone to organise the union. That working men might yet be free. Where oh where is the Citizen Army? Where oh where are those fighting men? They've gone to join the Great Rebellion, And break the bonds of slavery. And who'll be there to lead the van? Oh who'll be there to lead the van? Who should be there but our James Connolly, The hero of each working man. Who carries high that burning flag? Who carries high that burning flag? 'Tis our James Connolly all pale and wounded, Who carries high our burning flag. They carried him up to the jail. They carried him up to the jail. And there they shot him one bright May morning, And quickly laid him in his grave. Who mourns now for our James Connolly? Who mourns for the fighting man? Oh lay me down in yon green garden, And make my bearers Union men. We laid him down in yon green garden, With Union men on every side, And swore we'd make one mighty Union, And fill that gallant man with pride. Now all you noble Irishmen, Come join with me for liberty. And we will forge a mighty weapon, And smash the bonds of slavery!Listen to James Connolly from: Ron Kavana, Patsy Watchorn

Watch James Connolly from: Patrick Galvin, Andy Irvine, Fergus Russell

The only substantial combat of the first day of the Rising took place at the South Dublin Union where a piquet from the Royal Irish Regiment encountered an outpost of Éamonn Ceannt's force at the north-western corner of the South Dublin Union. The British troops, after taking some casualties, managed to regroup and launch several assaults on the position before they forced their way inside and the small rebel force in the tin huts at the eastern end of the Union surrendered. However, the Union complex as a whole remained in rebel hands.

Three unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police were shot dead on the first day of the Rising and their Commissioner pulled them off the streets. Partly as a result of the police withdrawal, a wave of looting broke out in the city centre, especially in the O'Connell Street area. A total of 425 people were arrested after the Rising for looting.

Lord Wimborne, the Lord Lieutenant, declared martial law on Tuesday evening and handed over civil power to Brigadier-General William Lowe. British forces initially put their efforts into securing the approaches to Dublin Castle and isolating the rebel headquarters, which they believed was in Liberty Hall. The British commander, Lowe, worked slowly, unsure of the size of the force he was up against, and with only 1,269 troops in the city when he arrived from the Curragh Camp in the early hours of Tuesday 25 April. City Hall was taken from the rebel unit that had attacked Dublin Castle on Tuesday morning.

The rebels had failed to take either of Dublin's two main train stations or either of its ports, at Dublin Port and Kingstown. As a result, during the following week, the British were able to bring in thousands of reinforcements from England and from their garrisons at the Curragh and Belfast. By the end of the week, British strength stood at over 16,000 men. Their firepower was provided by field artillery summoned from their garrison at Athlone which they positioned on the northside of the city at Phibsborough and at Trinity College, and by the patrol vessel Helga, which sailed up the Liffey, having been summoned from the port at Kingstown. On Wednesday, 26 April, the guns at Trinity College and Helga shelled Liberty Hall, and the Trinity College guns then began firing at rebel positions, first at Boland's Mill and then in O'Connell Street.

The principal rebel positions at the GPO, the Four Courts, Jacob's Factory and Boland's Mill saw little combat. The British surrounded and bombarded them rather than assault them directly. One Volunteer in the GPO recalled, "we did practically no shooting as there was no target". Similarly, the rebel position at St Stephen's Green, held by the Citizen Army under Michael Mallin, was made untenable after the British placed snipers and machine guns in the Shelbourne Hotel and surrounding buildings. As a result, Mallin's men retreated to the Royal College of Surgeons building where they remained for the rest of the week. However, where the insurgents dominated the routes by which the British tried to funnel reinforcements into the city, there was fierce fighting.

Reinforcements were sent to Dublin from England, and disembarked at Kingstown on the morning of 26 April. Heavy fighting occurred at the rebel-held positions around the Grand Canal as these troops advanced towards Dublin. The Sherwood Foresters were repeatedly caught in a cross-fire trying to cross the canal at Mount Street. Seventeen Volunteers were able to severely disrupt the British advance, killing or wounding 240 men. Despite there being alternative routes across the canal nearby, General Lowe ordered repeated frontal assaults on the Mount Street position. The British eventually took the position, which had not been reinforced by the nearby rebel garrison at Boland's Mills, on Thursday but the fighting there inflicted up to two thirds of their casualties for the entire week for a cost of just four dead Volunteers.

The rebel position at the South Dublin Union (site of the present day St. James's Hospital) and Marrowbone Lane, further west along the canal, also inflicted heavy losses on British troops. The South Dublin Union was a large complex of buildings and there was vicious fighting around and inside the buildings. Cathal Brugha, a rebel officer, distinguished himself in this action and was badly wounded. By the end of the week, the British had taken some of the buildings in the Union, but others remained in rebel hands. British troops also took casualties in unsuccessful frontal assaults on the Marrowbone Lane Distillery.

The third major scene of combat during the week was at North King Street, behind the Four Courts, where the British, on Thursday, tried to take a well-barricaded rebel position. By the time of the rebel headquarter's surrender, the South Staffordshire Regiment under Colonel Taylor had advanced only 150 yd (140 m) down the street at a cost of 11 dead and 28 wounded. The enraged troops broke into the houses along the street and shot or bayonetted 15 male civilians whom they accused of being rebel fighters.

Elsewhere, at Portobello Barracks, an officer named Bowen Colthurst summarily executed six civilians, including the pacifist nationalist activist, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington. These instances of British troops killing Irish civilians would later be highly controversial in Ireland.

The headquarters garrison at the GPO, after days of shelling, was forced to abandon their headquarters when fire caused by the shells spread to the GPO. Connolly had been incapacitated by a bullet wound to the ankle and had passed command on to Pearse. The O'Rahilly was killed in a sortie from the GPO. They tunnelled through the walls of the neighbouring buildings in order to evacuate the Post Office without coming under fire and took up a new position in 16 Moore Street. On Saturday 29 April, from this new headquarters, after realising that they could not break out of this position without further loss of civilian life, Pearse issued an order for all companies to surrender. Pearse surrendered unconditionally to Brigadier-General Lowe. The surrender document read:

In order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin citizens, and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered, the members of the Provisional Government present at headquarters have agreed to an unconditional surrender, and the commandants of the various districts in the City and County will order their commands to lay down arms.

James Connolly (II) A great crowd had gathered Outside of Kilmainhaim, With their heads uncovered they knelt on the ground, For inside that grim prison lay a brave Irish Soldier, His life for his Country about to lay down, He Went to his death like a true son of Ireland, The firing party he bravely did face, Then the order rang out: "Present arms, fire," James Connolly fell into a ready made grave. The black flag they hoisted, the cruel deed was over, Gone was a man who loved Ireland so well, There was many a sad heart in Dublin that morning, When they murdered James Connolly, the Irish Rebel. God's curse on you England, you cruel-hearted monster Your deeds they would shame all the devils in Hell There are no flowers blooming but the shamrock is growing On the grave of James Connolly, the Irish Rebel, Many years have rolled by since that Irish rebellion, When the guns of Britannia they loudly did speak. The bold IRA they stood shoulder to shoulder And the blood from their bodies flowed down Sackville Street The Four Courts of Dublin the English bombarded, The spirit of freedom they tried hard to quell, But above all the din rose the cry "No Surrender", 'Twas the voice of James Connolly, the Irish Rebel.Watch James Connolly from: Johnny McEvoy, Margo O'Donnell, Wolf Tones

The GPO was the only major rebel post to be physically taken during the week. The others surrendered only after Pearse's surrender order, carried by a nurse named Elizabeth O'Farrell, reached them. Sporadic fighting therefore continued until Sunday, when word of the surrender was got to the other rebel garrisons. Command of British forces had passed from Lowe to General John Maxwell, who arrived in Dublin just in time to take the surrender. Maxwell was made temporary military governor of Ireland.

Irish Volunteer units mobilised on Easter Sunday in several places outside of Dublin, but due to Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order, most of them returned home without fighting. In addition, due to the interception of the German arms aboard the Aud, the provincial Volunteer units were very poorly armed.

In the south, around 1,200 Volunteers mustered in Cork, under Tomás Mac Curtain on the Sunday, but they dispersed after receiving nine contradictory orders by dispatch from the Volunteer leadership in Dublin. Much to the anger of many Volunteers, MacCurtain, under pressure from Catholic clergy, agreed to surrender his men's arms to the British on Wednesday. The only violence in Cork occurred when the Kent family resisted arrest by the RIC, shooting one. One brother was killed in the shootout and another later executed.

Similarly, in the north, several Volunteer companies were mobilised at Coalisland in County Tyrone including 132 men from Belfast led by IRB President Dennis McCullough. However, in part due to the confusion caused by the countermanding order, the Volunteers there dispersed without fighting.

The only large-scale engagement outside the city of Dublin occurred at Ashbourne, County Meath. The Volunteers′ Dublin Brigade, 5th Battalion (also known as the Fingal Battalion), led by Thomas Ashe and his second in command Richard Mulcahy, composed of some 60 men, mobilised at Swords, where they seized the RIC Barracks and the Post Office. They did the same in the nearby villages of Donabate and Garristown before attacking the RIC barracks at Ashtown.

During the attack on the barracks, an RIC patrol from Slane happened upon the firefight – leading to a five-hour gun battle, in which eight RIC constables were killed and 15 wounded. Two Volunteers were also killed and five wounded. One civilian was also mortally wounded. Ashe's men camped at Kilsalaghan, near Dublin until they received orders to surrender on Saturday.

Volunteer contingents also mobilised nearby in counties Meath and Louth, but proved unable to link up with the North Dublin unit until after it had surrendered. In County Louth, Volunteers shot dead an RIC man near the village of Castlebellingham on 24 April, in an incident in which 15 RIC men were also taken prisoner.

In County Wexford, some 100 Volunteers led by Robert Brennan, Seamus Doyle and J R Etchingham took over Enniscorthy on Thursday 27 April until the following Sunday. They made a brief and unsuccessful attack on the RIC barracks, but unable to take it, resolved to blockade it instead. During their occupation of the town, they made such gestures as flying the tricolour over the Atheneum theatre, which they had made their headquarters, and parading uniformed in the streets.

A small party set off for Dublin, but turned back when they met a train full of British troops (part of a 1,000-strong force, which included the Connaught Rangers) on their way to Enniscorthy. On Saturday, two Volunteer leaders were escorted by the British to Arbour Hill Prison, where Pearse ordered them to surrender.

In the west, Liam Mellows led 600–700 Volunteers in abortive attacks on several police stations, at Oranmore and Clarinbridge in County Galway. There was also a skirmish at Carnmore in which one RIC man (Constable Patrick Whelan) was killed. However, his men were poorly armed, with only 25 rifles and 300 shotguns, many of them being equipped only with pikes. Toward the end of the week, Mellows′ followers were increasingly poorly fed and heard that large British reinforcements were being sent westwards. In addition, the British cruiser HMS Gloucester arrived in Galway Bay and shelled the fields around Athenry where the rebels were based.

On 29 April, the Volunteers, judging the situation to be hopeless, dispersed from the town of Athenry. Many of these Volunteers were arrested in the period following the rising, while others, including Mellows had to go "on the run" to escape. By the time British reinforcements arrived in the west, the rising there had already disintegrated.

The British Army reported casualties of 116 dead, 368 wounded and nine missing. Sixteen policemen died, and 29 were wounded. Rebel and civilian casualties were 318 dead and 2,217 wounded. The Volunteers and ICA recorded 64 killed in action, but otherwise Irish casualties were not divided into rebels and civilians. All 16 police fatalities and 22 of the British soldiers killed were Irishmen. British families came to Dublin Castle in May 1916 to reclaim the bodies and funerals were arranged. British bodies which were not claimed were given military funerals in Grangegorman Military Cemetery.

The majority of the casualties, both killed and wounded, were civilians. Both sides, British and rebel, shot civilians deliberately on occasion when they refused to obey orders such as to stop at checkpoints. On top of that, there were two instances of British troops killing civilians out of revenge or frustration, at Portobello Barracks, where six were shot and North King Street, where 15 were killed.

Grace As we gather in the chapel here in old Kilmainham Jaill I think about these past few weeks, oh will they say we've failed? From our school days they have told us we must yearn for liberty Yet all I want in this dark place is to have you here with me Oh Grace just hold me in your arms and let this moment linger They'll take me out at dawn and I will die With all my love I place this wedding ring upon your finger There won't be time to share our love for we must say goodbye Now I know it's hard for you my love to ever understand The love I shared for these brave men, the love for my dear land But when glory called me to his side down in the GPO I had to leave my own sick bed, to him I had to go Oh, Grace just hold me in your arms and let this moment linger They'll take me out at dawn and I will die With all my love I'll place this wedding ring upon your finger There won't be time to share our love for we must say goodbye Now as the dawn is breaking, my heart is breaking too On this May morn as I walk out, my thoughts will be of you And I'll write some words upon the wall so everyone will know I loved so much that I could see his blood upon the rose. Oh, Grace just hold me in your arms and let this moment linger They'll take me out at dawn and I will die With all my love I'll place this wedding ring upon your finger There won't be time to share our love for we must say goodbye For we must say goodbyeListen to Grace from: Jim McCann

Watch Grace from: The Dubliners, Jim McCann, The Wolfetones

However, the majority of civilian casualties were killed by indirect fire from artillery, heavy machine guns and incendiary shells. The British, who used such weapons extensively, therefore seem to have caused most non-combatant deaths. One Royal Irish Regiment officer recalled, "they regarded, not unreasonably, everyone they saw as an enemy, and fired at anything that moved".

General Maxwell quickly signalled his intention "to arrest all dangerous Sinn Feiners", including "those who have taken an active part in the movement although not in the present rebellion", reflecting the popular belief that Sinn Féin, a separatist organisation that was neither militant nor republican, was behind the Rising.

A total of 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested, although most were subsequently released. In attempting to arrest members of the Kent family in County Cork on 2 May, a Head Constable was shot dead in a gun battle. Richard Kent was also killed, and Thomas and William Kent were arrested.

In a series of courts martial beginning on 2 May, 90 people were sentenced to death. Fifteen of those (including all seven signatories of the Proclamation) had their sentences confirmed by Maxwell and were executed at Kilmainham Gaol by firing squad between 3 and 12 May (among them the seriously wounded Connolly, shot while tied to a chair due to a shattered ankle). Not all of those executed were leaders: Willie Pearse described himself as "a personal attaché to my brother, Patrick Pearse"; John MacBride had not even been aware of the Rising until it began, but had fought against the British in the Boer War fifteen years before; Thomas Kent did not come out at all—he was executed for the killing of a police officer during the raid on his house the week after the Rising. The most prominent leader to escape execution was Éamon de Valera, Commandant of the 3rd Battalion, who did so partly due to his American birth. The president of the courts martial was Charles Blackader.

1,480 men were interned in England and Wales under Regulation 14B of the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, many of whom, like Arthur Griffith, had little or nothing to do with the affair. Camps such as Frongoch internment camp became "Universities of Revolution" where future leaders like Michael Collins, Terence McSwiney and J. J. O'Connell began to plan the coming struggle for independence. The executions of those Rising leaders condemned to death took place over a nine-day period:

Sir Roger Casement was tried in London for high treason and hanged at Pentonville Prison on 3 August.

A Royal Commission was set up to enquire into the causes of the Rising. It began hearings on 18 May under the chairmanship of Lord Hardinge of Penshurst. The Commission heard evidence from Sir Matthew Nathan, Augustine Birrell, Lord Wimborne, Sir Neville Chamberlain (Inspector-General of the Royal Irish Constabulary), General Lovick Friend, Major Ivor Price of Military Intelligence and others. The report, published on 26 June, was critical of the Dublin administration, saying that "Ireland for several years had been administered on the principle that it was safer and more expedient to leave the law in abeyance if collision with any faction of the Irish people could thereby be avoided." Birrell and Nathan had resigned immediately after the Rising. Wimborne had also reluctantly resigned, recalled to London by Lloyd George, but was re-appointed in late 1917. Chamberlain resigned soon after.

At first, many members of the Dublin public were simply bewildered by the outbreak of the Rising. James Stephens, who was in Dublin during the week, thought, "None of these people were prepared for Insurrection. The thing had been sprung on them so suddenly they were unable to take sides."

There was considerable hostility towards the Volunteers in some parts of the city. When occupying positions in the South Dublin Union and Jacob's factory, the rebels got involved in physical confrontations with civilians trying to prevent them from taking over the buildings. The Volunteers' shooting and clubbing of civilians made them extremely unpopular in these localities. There was outright hostility to the Volunteers from the "separation women" (so-called because they were paid "Separation Money" by the British government), who had husbands and sons fighting in the British Army in World War I, and among unionists. Supporters of the Irish Parliamentary Party also felt the rebellion was a betrayal of their party.

That the Rising caused a great deal of death and destruction, as well as disrupting food supplies, also contributed to the antagonism toward the rebels. After the surrender, the Volunteers were hissed at, pelted with refuse, and denounced as "murderers" and "starvers of the people". Volunteer Robert Holland for example remembered being "subjected to very ugly remarks and cat-calls from the poorer classes" as they marched to surrender. He also reported being abused by people he knew as he was marched through the Kilmainham area into captivity and said the British troops saved them from being manhandled by the crowd.

However, there was not universal hostility towards the defeated insurgents. Some onlookers were cowed rather than hostile and it appeared to the Volunteers that some of those watching in silence were sympathetic. Canadian journalist and writer Frederick Arthur McKenzie wrote that in poorer areas, "there was a vast amount of sympathy with the rebels, particularly after the rebels were defeated." Thomas Johnson, the Labour leader, thought there was, "no sign of sympathy for the rebels, but general admiration for their courage and strategy."

Irish Spring My great great grandfather was a refugee From a place called Ireland He didn't want to leave home, but when you're a slave Nothing goes how you might have planned Like most of the island, he had nothing to eat He survived by going away But if he hadn't starved, and if he hadn't left Perhaps he would have lived to see the day When after centuries of subjugation Under English queens and kings Came the movement of the Irish Spring When things were set in motion around one Easter morning To move from colony to nation When through the foggy dew could be seen lines of marching men Heading towards a country's liberation Then a century ago, on April 24th Suddenly, one day the spell was broken For 6 days and nights, all across the island The spirit of resistance had spoken Quickly it was clear – even the deaf could hear The sounds of two armies battling And the bullets of the Irish Spring Buildings lay in ruins when the rebels had surrendered A battle lost – a war only begun Chains, once thrown off, don't go back on easily And soon the British Army was on the run The Dail convened and declared the Republic A nation among the others on the Earth A nation with a people, with a culture and a history Celebrated from Liverpool to Perth A nation with a memory That's in the songs it sings With the music of the Irish Spring A revolution left unfinished, you can hear many people say On the streets of Derry and Belfast But in all 32 counties you'll hear many people talking Of the struggles and the martyrs of the past Of those who dared stand up and teach us through example What it means sacrifice it all Of those who demonstrated if they believe that they are free Only then can they possibly stand tall Of Connolly and Pearse and all those who gave their lives That they might hear the bells of freedom ring With the rising of the Irish SpringWatch Irish Spring from: David Rovics

The aftermath of the Rising, and in particular the British reaction to it, helped sway a large section of Irish nationalist opinion away from hostility or ambivalence and towards support for the rebels of Easter 1916. Dublin businessman and Quaker James G. Douglas, for example, hitherto a Home Ruler, wrote that his political outlook changed radically during the course of the Rising due to the British military occupation of the city and that he became convinced that parliamentary methods would not be sufficient to remove the British presence.

A meeting called by Count Plunkett on 19 April 1917 led to the formation of a broad political movement under the banner of Sinn Féin which was formalised at the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis of 25 October 1917. The Conscription Crisis of 1918 further intensified public support for Sinn Féin before the general elections to the British Parliament on 14 December 1918, which resulted in a landslide victory for Sinn Féin, whose MPs gathered in Dublin on 21 January 1919 to form Dáil Éireann and adopt the Declaration of Independence.

Shortly after the Easter Rising, poet Francis Ledwidge wrote "O’Connell Street" and "Lament for the Poets of 1916," which both describe his sense of loss and an expression of holding the same "dreams", as the Easter Rising's Irish Republicans. He would also go on to write lament for Thomas MacDonagh for his fallen friend and fellow Irish Volunteer. A few months after the Easter Rising, W. B. Yeats commemorated some of the fallen figures of the Irish Republican movement, as well as his torn emotions regarding these events, in the poem Easter, 1916.

Some of the survivors of the Rising went on to become leaders of the independent Irish state. Those who were executed were venerated by many as martyrs; their graves in Dublin's former military prison of Arbour Hill became a national monument and the Proclamation text was taught in schools. An annual commemorative military parade was held each year on Easter Sunday, culminating in a huge national celebration on the 50th anniversary in 1966. RTÉ, the Irish national broadcaster, as one of its first major undertakings made a series of commemorative programmes for the 1966 anniversary of the Rising. Roibéárd Ó Faracháin, head of programming said, "While still seeking historical truth, the emphasis will be on homage, on salutation."

With the outbreak of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, government, academics and the media began to revise the country's militant past, and particularly the Easter Rising. The coalition government of 1973–77, in particular the Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, Conor Cruise O'Brien, began to promote the view that the violence of 1916 was essentially no different from the violence then taking place in the streets of Belfast and Derry.

O'Brien and others asserted that the Rising was doomed to military defeat from the outset, and that it failed to account for the determination of Ulster Unionists to remain in the United Kingdom.

Irish republicans continue to venerate the Rising and its leaders with murals in republican areas of Belfast and other towns celebrating the actions of Pearse and his comrades, and annual parades in remembrance of the Rising. The Irish government, however, discontinued its annual parade in Dublin in the early 1970s, and in 1976 it took the unprecedented step of proscribing (under the Offences against the State Act) a 1916 commemoration ceremony at the GPO organised by Sinn Féin and the Republican commemoration Committee. A Labour Party TD, David Thornley, embarrassed the government (of which Labour was a member) by appearing on the platform at the ceremony, along with Máire Comerford, who had fought in the Rising, and Fiona Plunkett, sister of Joseph Plunkett.

With the advent of a Provisional IRA ceasefire and the beginning of what became known as the Peace Process during the 1990s, the official view of the Rising grew more positive and in 1996 an 80th anniversary commemoration at the Garden of Remembrance in Dublin was attended by the Taoiseach and leader of Fine Gael, John Bruton. In 2005, the Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, announced the government's intention to resume the military parade past the GPO from Easter 2006, and to form a committee to plan centenary celebrations in 2016. The 90th anniversary was celebrated with a military parade in Dublin on Easter Sunday, 2006, attended by the President of Ireland, the Taoiseach and the Lord Mayor of Dublin. There is now an annual ceremony at Easter attended by relatives of those who fought, by the President, the Taoiseach, ministers, senators and TDs, and by usually large and respectful crowds.

In December 2014 Dublin City Council approved a proposal to create a historical path commemorating the Rising, similar to the Freedom Trail in Boston. Lord Mayor of Dublin Christy Burke announced that the council had committed to building the trail, marking it with a green line or bricks, with brass plates marking the related historic sites such as the Rotunda and the General Post Office.

The Easter Rising lasted from Easter Monday 24 April 1916 to Easter Saturday 29 April 1916. Annual commemorations, rather than taking place on 24–29 April, are typically based on the date of Easter, which is a moveable feast. For example, the annual military parade is on Easter Sunday; the date of coming into force of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 was symbolically chosen as Easter Monday (18 April) 1949. The official programme of centenary events in 2016 climaxes from 26 March (Good Friday) to 3 April (Easter Saturday) with other events earlier and later in the year taking place on the calendrical anniversaries.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

Date: February 2016.

Photo Credits:

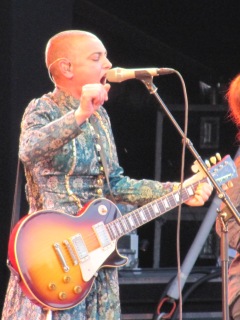

(1) 'The Foggy Dew',

(2) Ireland 2016: A Year for Everyone,

(4) Gráinne Holland,

(5) 'Mise Éire',

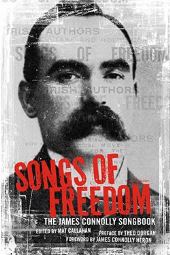

(6) Callahan 'Songs of Freedom - The James Connolly Songbook',

(7) Jim McCann,

(8) David Rovics

(unknown/website);

(3) Sinéad O'Connor,

(by Walkin' Tom).