|

The third night we were to pass through the western end of the country

of Balquhidder [5].

It came clear and cold, with a touch in the air like

frost, and a northerly wind that blew the clouds away and made the stars

bright.

As for me, the change of weather

came too late; I had lain in the mire so long that (as the Bible has it)

my very clothes "abhorred me." I was dead weary, deadly sick and full

of pains and shiverings; the chill of the wind went through me, and the

sound of it confused my ears.

I felt I could drag myself but little farther; pretty soon, I

must lie down and die on these wet mountains like a sheep or a fox, and

my bones must whiten there like the bones of a beast.

At the door of the first house we came to, Alan knocked, which was of

no very safe enterprise in such a part of the Highlands as the Braes of

Balquhidder.

No great clan held rule there; it was filled and disputed

by small septs, and broken remnants, and what they call "chiefless

folk," driven into the wild country about the springs of Forth and Teith

by the advance of the Campbells. Here were Stewarts and Maclarens, which

came to the same thing, for the Maclarens followed Alan's chief in war,

and made but one clan with Appin. Here, too, were many of that old,

proscribed, nameless, red-handed clan of the Macgregors. They had always

been ill-considered, and now worse than ever, having credit with no side

or party in the whole country of Scotland. Their chief, Macgregor of

Macgregor, was in exile; the more immediate leader of that part of them

about Balquhidder, James More, Rob Roy's eldest son, lay waiting his

trial in Edinburgh Castle; they were in ill-blood with Highlander and

Lowlander, with the Grahames, the Maclarens, and the Stewarts; and Alan,

who took up the quarrel of any friend, however distant, was extremely

wishful to avoid them.

Chance served us very well; for it was a household of Maclarens that we

found, where Alan was not only welcome for his name's sake but known

by reputation. Here then I was got to bed without delay, and a doctor

fetched, who found me in a sorry plight. But whether because he was a

very good doctor, or I a very young, strong man, I lay bedridden for no

more than a week, and before a month I was able to take the road again

with a good heart.

All this time Alan would not leave me though I often pressed him, and

indeed his foolhardiness in staying was a common subject of outcry with

the two or three friends that were let into the secret. He hid by day

in a hole of the braes under a little wood; and at night, when the coast

was clear, would come into the house to visit me. I need not say if I

was pleased to see him; Mrs. Maclaren, our hostess, thought nothing good

enough for such a guest; and as Duncan Dhu (which was the name of our

host) had a pair of pipes [6] in his house, and was much of a lover of

music, this time of my recovery was quite a festival, and we commonly

turned night into day.

The soldiers let us be; although once a party of two companies and some

dragoons went by in the bottom of the valley, where I could see them

through the window as I lay in bed. What was much more astonishing, no

magistrate came near me, and there was no question put of whence I came

or whither I was going; and in that time of excitement, I was as free of

all inquiry as though I had lain in a desert. Yet my presence was known

before I left to all the people in Balquhidder and the adjacent parts;

many coming about the house on visits and these (after the custom of the

country) spreading the news among their neighbours. The bills, too, had

now been printed. There was one pinned near the foot of my bed, where

I could read my own not very flattering portrait and, in larger

characters, the amount of the blood money that had been set upon my

life. Duncan Dhu and the rest that knew that I had come there in Alan's

company, could have entertained no doubt of who I was; and many others

must have had their guess. For though I had changed my clothes, I could

not change my age or person; and Lowland boys of eighteen were not so

rife in these parts of the world, and above all about that time, that

they could fail to put one thing with another, and connect me with the

bill. So it was, at least. Other folk keep a secret among two or three

near friends, and somehow it leaks out; but among these clansmen, it is

told to a whole countryside, and they will keep it for a century.

There was but one thing happened worth narrating; and that is the visit

I had of Robin Oig, one of the sons of the notorious Rob Roy [7]. He was

sought upon all sides on a charge of carrying a young woman from

Balfron and marrying her (as was alleged) by force; yet he stepped about

Balquhidder like a gentleman in his own walled policy. It was he who had

shot James Maclaren at the plough stilts, a quarrel never satisfied; yet

he walked into the house of his blood enemies as a rider [8] might into a

public inn.

Duncan had time to pass me word of who it was; and we looked at one

another in concern. You should understand, it was then close upon the

time of Alan's coming; the two were little likely to agree; and yet if

we sent word or sought to make a signal, it was sure to arouse suspicion

in a man under so dark a cloud as the Macgregor.

He came in with a great show of civility, but like a man among

inferiors; took off his bonnet to Mrs. Maclaren, but clapped it on his

head again to speak to Duncan; and leaving thus set himself (as he would

have thought) in a proper light, came to my bedside and bowed.

"I am given to know, sir," says he, "that your name is Balfour."

"They call me David Balfour," said I, "at your service."

"I would give ye my name in return, sir" he replied, "but it's one

somewhat blown upon of late days; and it'll perhaps suffice if I tell

ye that I am own brother to James More Drummond or Macgregor, of whom ye

will scarce have failed to hear."

"No, sir," said I, a little alarmed; "nor yet of your father,

Macgregor-Campbell." And I sat up and bowed in bed; for I thought best

to compliment him, in case he was proud of having had an outlaw to his

father.

He bowed in return. "But what I am come to say, sir," he went on, "is

this. In the year '45, my brother raised a part of the 'Gregara' and

marched six companies to strike a stroke for the good side; and the

surgeon that marched with our clan and cured my brother's leg when it

was broken in the brush at Preston Pans [9], was a gentleman of the same

name precisely as yourself. He was brother to Balfour of Baith; and if

you are in any reasonable degree of nearness one of that gentleman's

kin, I have come to put myself and my people at your command."

You are to remember that I knew no more of my descent than any cadger's

dog; my uncle, to be sure, had prated of some of our high connections,

but nothing to the present purpose; and there was nothing left me but

that bitter disgrace of owning that I could not tell.

Robin told me shortly he was sorry he had put himself about, turned his

back upon me without a sign of salutation, and as he went towards the

door, I could hear him telling Duncan that I was "only some kinless loon

that didn't know his own father." Angry as I was at these words, and

ashamed of my own ignorance, I could scarce keep from smiling that a

man who was under the lash of the law (and was indeed hanged some three

years later) should be so nice as to the descent of his acquaintances.

Just in the door, he met Alan coming in; and the two drew back and

looked at each other like strange dogs. They were neither of them big

men, but they seemed fairly to swell out with pride. Each wore a sword,

and by a movement of his haunch, thrust clear the hilt of it, so that it

might be the more readily grasped and the blade drawn.

"Mr. Stewart, I am thinking," says Robin.

"Troth [10], Mr. Macgregor, it's not a name to be ashamed of," answered Alan.

"I did not know ye were in my country, sir," says Robin.

"It sticks in my mind that I am in the country of my friends the

Maclarens," says Alan.

"That's a kittle [11] point," returned the other. "There may be two words to

say to that. But I think I will have heard that you are a man of your

sword?"

"Unless ye were born deaf, Mr. Macgregor, ye will have heard a good deal

more than that," says Alan. "I am not the only man that can draw steel

in Appin; and when my kinsman and captain, Ardshiel [12], had a talk with a

gentleman of your name, not so many years back, I could never hear that

the Macgregor had the best of it."

"Do ye mean my father, sir?" says Robin.

"Well, I wouldnae wonder," said Alan. "The gentleman I have in my mind

had the ill-taste to clap Campbell to his name."

"My father was an old man," returned Robin. "The match was unequal. You and me would make a better pair, sir."

"I was thinking that," said Alan.

I was half out of bed, and Duncan had been hanging at the elbow of these

fighting cocks, ready to intervene upon the least occasion. But when

that word was uttered, it was a case of now or never; and Duncan, with

something of a white face to be sure, thrust himself between.

"Gentlemen," said he, "I will have been thinking of a very different

matter, whateffer. Here are my pipes, and here are you two gentlemen who

are baith acclaimed pipers. It's an auld dispute which one of ye's the

best. Here will be a braw [13] chance to settle it."

"Why, sir," said Alan, still addressing Robin, from whom indeed he had

not so much as shifted his eyes, nor yet Robin from him, "why, sir,"

says Alan, "I think I will have heard some sough [14] of the sort. Have ye

music, as folk say? Are ye a bit of a piper?"

"I can pipe like a Macrimmon!" cries Robin. [15]

"And that is a very bold word," quoth Alan.

"I have made bolder words good before now," returned Robin, "and that

against better adversaries."

"It is easy to try that," says Alan.

Duncan Dhu made haste to bring out the pair of pipes that was his

principal possession, and to set before his guests a mutton-ham and a

bottle of that drink which they call Athole brose, and which is made of

old whiskey, strained honey and sweet cream, slowly beaten together in

the right order and proportion. The two enemies were still on the very

breach of a quarrel; but down they sat, one upon each side of the peat

fire, with a mighty show of politeness. Maclaren pressed them to taste

his mutton-ham and "the wife's brose," reminding them the wife was out

of Athole and had a name far and wide for her skill in that confection.

But Robin put aside these hospitalities as bad for the breath.

"I would have ye to remark, sir," said Alan, "that I havenae broken

bread for near upon ten hours, which will be worse for the breath than

any brose in Scotland."

"I will take no advantages, Mr. Stewart," replied Robin. "Eat and drink;

I'll follow you."

Each ate a small portion of the ham and drank a glass of the brose to

Mrs. Maclaren; and then after a great number of civilities, Robin took

the pipes and played a little spring [16] in a very ranting manner.

"Ay, ye can, blow" said Alan; and taking the instrument from his rival,

he first played the same spring in a manner identical with Robin's; and

then wandered into variations, which, as he went on, he decorated with

a perfect flight of grace-notes, such as pipers love, and call the

"warblers." [17]

I had been pleased with Robin's playing, Alan's ravished me.

"That's no very bad, Mr. Stewart," said the rival, "but ye show a poor

device in your warblers."

"Me!" cried Alan, the blood starting to his face. "I give ye the lie."

"Do ye own yourself beaten at the pipes, then," said Robin, "that ye

seek to change them for the sword?"

"And that's very well said, Mr. Macgregor," returned Alan; "and in the

meantime" (laying a strong accent on the word) "I take back the lie. I

appeal to Duncan."

"Indeed, ye need appeal to naebody," said Robin. "Ye're a far better

judge than any Maclaren in Balquhidder: for it's a God's truth that

you're a very creditable piper for a Stewart. Hand me the pipes." Alan

did as he asked; and Robin proceeded to imitate and correct some part of

Alan's variations, which it seemed that he remembered perfectly.

"Ay, ye have music," said Alan, gloomily.

"And now be the judge yourself, Mr. Stewart," said Robin; and taking up

the variations from the beginning, he worked them throughout to so new a

purpose, with such ingenuity and sentiment, and with so odd a fancy and

so quick a knack in the grace-notes, that I was amazed to hear him.

As for Alan, his face grew dark and hot, and he sat and gnawed his

fingers, like a man under some deep affront. "Enough!" he cried. "Ye can

blow the pipes--make the most of that." And he made as if to rise.

But Robin only held out his hand as if to ask for silence, and struck

into the slow measure of a pibroch [18]. It was a fine piece of music in

itself, and nobly played; but it seems, besides, it was a piece peculiar

to the Appin Stewarts and a chief favourite with Alan. The first notes

were scarce out, before there came a change in his face; when the time

quickened, he seemed to grow restless in his seat; and long before that

piece was at an end, the last signs of his anger died from him, and he

had no thought but for the music.

"Robin Oig," he said, when it was done, "ye are a great piper. I am not

fit to blow in the same kingdom with ye. Body of me! ye have mair [19] music

in your sporran [20] than I have in my head! And though it still sticks in

my mind that I could maybe show ye another of it with the cold steel,

I warn ye beforehand--it'll no be fair! It would go against my heart to

haggle a man that can blow the pipes as you can!"

Thereupon that quarrel was made up; all night long the brose was going

and the pipes changing hands; and the day had come pretty bright, and

the three men were none the better for what they had been taking, before

Robin as much as thought upon the road.

The round-house was like a shambles; three were dead inside, another

lay in his death agony across the threshold; and there were Alan and I

victorious and unhurt.

He came up to me with open arms. "Come to my arms!" he cried, and

embraced and kissed me hard upon both cheek. "David," said he, "I love

you like a brother. And O, man," he cried in a kind of ecstasy, "am I no

a bonny fighter?"

Thereupon he turned to the four enemies, passed his sword clean through

each of them, and tumbled them out of doors one after the other. As he

did so, he kept humming and singing and whistling to himself, like a man

trying to recall an air; only what he was trying was to make one. All

the while, the flush was in his face, and his eyes were as bright as a

five-year-old child's with a new toy. And presently he sat down upon the

table, sword in hand; the air that he was making all the time began to

run a little clearer, and then clearer still; and then out he burst with

a great voice into a Gaelic song.

I have translated it here, not in verse (of which I have no skill) but

at least in the king's English.

He sang it often afterwards, and the thing became popular; so that I

have heard it, and had it explained to me, many's the time.

This is the song of the sword of Alan:

The smith made it,

The fire set

it;

Now it shines in the hand of Alan Breck.

Their eyes were many and bright,

Swift were they to behold,

Many the

hands they guided:

The sword was alone.

The dun deer troop over the hill,

They are many, the hill is one;

The

dun deer vanish,

The hill remains.

Come to me from the hills of heather,

Come from the isles of the sea.

O

far-beholding eagles,

Here is your meat.

|

Footnotes:

[1]

Kidnapped is an adventure novel by the Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson, first published in the Young Folks magazine in 1886. The story involves the young David Balfour who goes to live with his uncle Ebenezer after his father has died. Ebenezer, who has illegitimately acquired the Balfour estate, has David kidnapped. David finds himself on a ship to the Carolinas accompanied by the Jacobite [3] rebel Alan Breck Stewart [2]. The ship is wrecked on the rocks at Mull, David and Alan wander across the Scottish Highlands, after witnessing and becoming suspects in the murder of Colin Campbell (which is historical but actually occured in 1752 [2]). "Kidnapped" has been repeatedly made into a movie picture. The 1960 version includes the Quarrel, starring Peter O'Toole as Robin Oig and Peter Finch as Alan Breck.

More about the novel @ Wikipedia;

full text @ Wikipedia,

Gutenberg,

UndiscoveredScotland;

maps of the journey @ Wikipedia,

UndiscoveredScotland.

[2] The real Alan Breck Stewart (breck: freckled or pock marked) grew up under the care of his relative James Stewart (known as Seumas a' Ghlinne: James of the Glen) at the Appin peninsula at Loch Linnhe. Alan Breck enlisted in the British Army in 1745 and fought at Prestonpans [9]. He changed sides and subsequently fought for the Jacobites at Culloden [3]. Afterwards he fled to France, joining one of the Scottish regiments serving in the French Army. Alan Breck was given the job of returning to Scotland to collect rents for the exiled clan leaders. On 14 May 1752, Colin Campbell, the Red Fox of Glenure, was killed in the woods between Ballachulish and Lettermore. Since Alan Breck had previously threatened Campbell, a warrant was issued for his arrest. He evaded capture, James of the Glen was hanged. Sir Walter Scott claimed to have met the elderly Alan Breck and gather information for his novel "Rob Roy" [7]. Alan Breck also has a cameo role in Stevenson's novel "The Master of Ballantrae".

When Charlie first cam' tae the North

With the manly look o' a Highland laddie

He turned every true Scot tae himsel'

Tae view the lad an' his tartan plaidie

When King Geordie heard o' this

That he had gaen North tae wi for his daddy

He sent John Cope up tae the North

Tae catch the lad an' the tartan plaidie

On Prestonpans he formed his clans

He neither regarded son nor daddy

Like the wind o' the sky he made them tae fly

Wi' every shake o' his tartan plaidie

|

[3]

According to The Tannahill Weavers, Jacobites are not a crunchy cat food, but the followers of the Stuarts. Jacobitism was the political movement dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England and Scotland. The movement took its name from the Latin form of James. In 1688 King James II was replaced by William of Orange. The Stuarts lived on the European mainland ever since. In 1745 Charles Edward Stuart landed in west Scotland and led the (second) Jacobite Rising - whereupon the Highland Scots led by a Frenchman (Bonnie Prince Charlie) fought against the English led by a German (George of the House of Hannover). On 16 April 1746, Charles and the Highland army were defeated at the Battle of Culloden.

More @ Wikipedia,

BritishBattles,

CullodenHome.

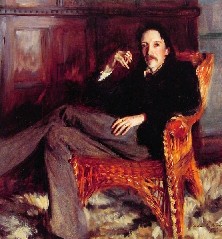

[4] Robert Louis Stevenson was born in Edinburgh in 1850.

He spent much of his life battling a severe lung disease

and travelled constantly in search of a healthy climate.

He died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Samoa in 1894.

Stevenson is best remembered for his novels of romantic adventure.

The publication of "Treasure Island" in 1883 brought him enormous acclaim.

He enhanced his reputation with "The Black Arrow",

"The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde", "Kidnapped" and

"The Master of Ballantrae".

Stevenson is best remembered for his novels of romantic adventure.

The publication of "Treasure Island" in 1883 brought him enormous acclaim.

He enhanced his reputation with "The Black Arrow",

"The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde", "Kidnapped" and

"The Master of Ballantrae".

More @ Wikipedia.

[5] The Braes of Balquhidder (brae: hill) lie near Loch Voil, west of the A84. Balquhidder (pronounced bal'-whither) comes from the Gaelic Baile-chuil-tir which means the distant farm.

More @

UndiscoveredScotland.

Robert Tannahill's song "The Braes o' Balquhidder" is the original form of "Wild Mountain Thyme."

More @

ScotsIndependent,

Chivalry.

Will ye go, lassie, go,

to the braes o' Balquhidder

Where the blaeberries grow

'mang the bonnie bloomin' heather

Now the summer is in prime,

wi' the flowers richly bloomin'

An' the wild mountain thyme

a' the moorlands perfumin'

|

Bagpipes, not lyres, the Highland hills adorn ...

The piper came to our town, and he played bonnielie

He play'd a spring the laird to please

A spring brent new from 'yont the seas

And then he gae his bags a wheeze

and played anither key

|

[6]

Tha ceol 'sna maidean, ma bheir thus' as e. -

There's music in the sticks, if you can draw it out.

Bagpipes are aerophones using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air. The modern Great Highland Bagpipe (Gaelic: pìob mòr) has a bag, a chanter, a blowpipe, two tenor drones, and one bass drone. Bagpipes were probably developed from an instrument similar to a hornpipe or a shawm. The earliest reference occurs when the Greek poet Aristophones ridicules that the pipers of Thebes blew pipes made of dogskin with chanters made of bone. As a bagpipe with drone accompaniment, it became common from the 12th century. Robert the Bruce's army marched to Bannockburn in 1314 to a popular pipe tune (of which Robert Burns later wrote "Scots wha hae"). A carving in stone on Melrose Abbey of a pig playing a bagpipe dates from 1385. In the 16th century, pipers displaced the harpers in the Scottish Highlands. Despite claims that the bagpipe was banned after 1745, there is no evidence. However, on 15th November 1746, piper James Reid was executed as a rebel though he had not carried arms. The court observed that a Highland regiment never marched without a piper and therefore that his bagpipe was an instrument of war. With the growth of the British Empire, Scottish regiments and their pipe bands gained worldwide renown. Its use has become a common tradition for funerals and memorials.

More @

Wikipedia.

European Bagpipes, left to right: Xose Manuel Budino, Susane Seivane, Yves Barbieux, Bub, Hevia.

|

[7]

Rob Roy MacGregor (ruadh: red) was born in 1671 at Glengyle in the Trossachs. Rob Roy (who used his mother's name of Campbell, the MacGregor name had been proscribed in 1603) set up a cattle business. He married his cousin Mary Helen MacGregor and they subsequently had four sons: James Mor, Ranald, Coll, and Robin Oig. In 1711 Rob Roy borrowed £1,000 from the Duke of Montrose to purchase cattle, but his head drover disappeared with the funds. Rob Roy's lands were seized and his family evicted by Montrose, so he started a career as an outlaw. He was eventually captured and sentenced to be transported. However, due to Daniel Defoe's popular biography "Highland Rogue" (1723) he was pardoned by public acclaim in 1726. Rob Roy died in 1734 and is buried in Balquhidder kirkyard. Sir Walter Scott wrote a novel about him (1817), and he was the subject of two Hollywood films.

More @ UndiscoveredScotland.

McGregor o' the heilan' clan ye left five sons and no' a man

Your motley crew dae a' they can tae terrorise the border

The gallows noo will have its chance, Jamie fled awa' tae France

He'll no' be here tae see Rab dance, in Hell they'll meet thegither

|

[8] rider: commercial traveller.

Alan had stopped opposite to me, his hat cocked, his hands in his

breeches pockets, his head a little on one side. He listened, smiling

evilly, as I could see by the starlight; and when I had done he began to

whistle a Jacobite air. It was the air made in mockery of General Cope's

defeat at Preston Pans:

Hey, Johnnie Cope, are ye waukin' yet?

And are your drums a-beatin' yet?

|

[9]

Prestonpans is a small town east of Edinburgh. It is the site of the Battle of Prestonpans on 21 September 1745 where the Jacobite army defeated the English led by Sir John Cope.

It had been claimed that Cope made a disgraceful retreat from the battlefield.

However, Cope was acquitted at a court-martial and died as a Lieutenant-General in 1760.

More @

Wikipedia,

HeritageTrust,

BritishBattles.

The local farmer Adam Skirving (1719-1803) wrote two popular songs: "Hey, Johnnie Cope, Are Ye Waukin' Yet" is a catchy insult to Cope, "Tranent Muir" is a historically accurate description of the battle. A Lieutenant Smith, described as fleeing the battle in dread, challenged Skirving to a duel after the song was published. Smith despatched a junior officer to Skirving bearing the challenge to meet him. Skirving replied: Gang back and tell Lt. Smith that I have nae leisure to come to Haddington; but tell him to come here and I'll tak' a look at him, and if I think I am fit to fecht him, I'll fecht him; if no, I'll do as he did - I'll rin awa'.

More @

MySongbook,

Contemplator.

[10] troth: short for by my troth: faithfulness, fidelity.

[11] kittle: tickle (in the English variant spoken in Lowland Scotland, more @ ScotsOnline).

[12] Charles Stewart of Ardshiel led the Appin Stewarts in the Jacobite rising of 1745.

[13] braw: fine.

No more, no more, no more forever

In war or peace shall return MacCrimmon

No more, no more, no more forever

Shall love or gold bring back MacCrimmon

Behind the bard came the Piper, ready to fill his bag and finger his chanter at a nod

from the chief. He too was a gentleman among gentlemen, who held his post from his

father and who came from a long line of pipers. His name could sometimes live longer

than the chief he served. The greatest of all pipers in all the Highlands were the

MacCrimmons, who could make men weep or fight like the gods just by an inflated bag

and a flute of bone. The piper sat on no hill when the clan was for the onslaught,

but marched behind the chief with the drones spread, and his wild music calling up

the rant and the red reminders of past valour. (J. Prebble)

Selected Discography:

The Great Highland Bagpipe,

Piping Up,

The Piping Centre,

The Piper & The Maker

|

[14] sough: rumour.

[15]

Air na piobairean uile, b'e Mac Cruimein an Righ. - Of all pipers MacCrimmon was king. The MacCrimmons were hereditary pipers to the MacLeods of Dunvegan, Isle of Skye, and the most famous piping family in Scotland.

Under MacLeod's patronage they formed a school of piping at Borreraig from

1500 to 1800, where apprentices were taught music, dancing, sword play and the history of their clans.

The lament "The Piper's Weird" (weird: destiny) is said to have been written by Donald Ban MacCrimmon who predicted his own death at Culloden;

"MacCrimmon's Lament" is a folksong variant from the 19th century.

More @ MySongbook.

[16] spring: a lively tune or dance.

[17]

The Great Highland Bagpipe is limited by its range (nine notes), lack of dynamics (ability to change the volume), and lack of rests. The latter due to the fact that the airflow to the reeds is continuous. Notes cannot be separated by simply stop blowing. So grace-notes and embellishments are used, sometimes called warblers (or variously: cuts, cuttings, doublings, throws, grips, birls, taorluath, crunluath, ...). All grace-notes are performed by quick finger movements, giving an effect similar to tonguing or articulation on modern wind instruments.

[18]

The Gaelic word pìobaireachd (pibroch) simply means pipe music,

but usually relates to what nowadays is called ceòl mòr (great music), opposed to ceòl beag (little music: marches, dance tunes, airs). Pibrochs include laments for a deceased person of note, salutes to acknowledge a person, event or location, and gatherings that were used to call a clan together by their chief. A pibroch consists of a slow ground movement (ùrlar) which is a simple theme, then a series of increasingly complex variations on this theme, and ends with a return to the ground.

The ceòl mòr style was developed by the bagpipe dynasties such as the MacCrimmons and emerged as a distinct form during the 17th century.

More @ Wikipedia.

[19] mair: more.

[20] A sporran is a pouch worn on a chain or belt around the waist, now a decorative part of the Highland dress.

|