Smithsonian Folkways Celebrates the Legacy & Cultural Impact of Hazel Dickens & Alice Gerrard with Reissue Campaign Featuring Previously Unheard Louvin Brothers Cover.

The music that Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard recorded together beginning in 1965 has influenced generations of musicians across genres, primarily women, from Emmylou Harris and the Judds up through Kathleen Hanna, Alison Krauss and Rhiannon Giddens. "The harmony was so bold," Naomi Judd told the Washington Post years ago. "They were unabashedly just who they were -- it was really like looking in the mirror of truth. We felt like we knew them, and when we listened to the songs, it crystallized the possibility that two women could sing together.” Bluegrass icon Claire Lynch says that “Hazel and Alice were the first ‘voices’ I heard in bluegrass music that sang on women’s behalf” and young guitar-slinging singer/songwriter Molly Tuttle says, “I first heard Hazel and Alice when I was 12 years old, and their music changed my life.”

Their influence will continue to reverberate when, on October 21, Smithsonian Folkways releases newly remastered editions of their first two albums Who's That Knocking? and Won't You Come and Sing for Me? which have been unavailable on vinyl for over 40 years. The original song sequences of these two albums will also be available on streaming services and as downloads for the first time ever.

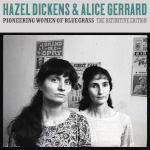

On the same day, Folkways will also be releasing (via streaming and CD) Pioneering Women of Bluegrass: The Definitive Edition, which for the first time collects every track recorded by Dickens and Gerrard for Folkways, as well as a previously unheard bonus track. The new CD features comprehensive track-by-track notes and an expanded essay by Gerrard herself, still going strong at age 88, as well as an essay by Dickens, who passed away in 2011. New liner notes by Laurie Lewis and Peter K. Siegel and new pictures by celebrated photographers John Cohen and Carl Fleischhauer complete the 32-page CD booklet.

Peter K. Siegel, who engineered and recorded all the original songs in the 1960s, remastered the CD, which also includes a never-heard track, “Childish Love” originally sung by the Louvin Brothers. The track is available to stream today. This track was recorded in the 1960s but kept in the vaults due to then-insurmountable technical difficulties. “When those albums first came out, I was disappointed with the quality of the sound,” Siegel writes in the liner notes. “I think the new masters better capture the essence of Hazel and Alice’s music, and sound more like the traditional bluegrass style that these performances represent.”

These reissues come during a time of renewed interest in Gerrard’s music and history. She released a Grammy-nominated late-period career highlight Follow The Music, which was recorded with Hiss Golden Messenger’s MC Taylor, in 2014. She has continued to perform, most recently singing songs of resistance at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall on the day the recent controversial Dobbs opinion on abortion was handed down.

In an era where the role of women in many genres and artforms is being reevaluated and highlighted anew, these iconic recordings tell the story of two women whose inventiveness, conviction, and grit allowed them access to stages, audiences, and a legacy previously only afforded to men. After Hazel and Alice entered the picture, bluegrass would never be the same.

Dickens and Gerrard both grew up in musical families: Dickens, in West Virginia, learned the raw, unaccompanied singing style of coal country, while Gerrard, in Seattle, became immersed in the classical music of her college-educated parents. Despite their different musical backgrounds, they were both drawn to the flourishing house picking-party scene in the Baltimore-Washington area, where many of its urban movers and shakers sought out the authentic, traditional music of Appalachian migrants. They first met within that scene in their 20s, but at the time, the few women playing bluegrass music tended to appear primarily as part of family acts. For Dickens and Gerrard, it would take the better part of a decade for their playing to appear on a record.

“Sometime in 1964, Peter Siegel and David Grisman heard Hazel and me singing at a party in D.C. and suggested we record,” Gerrard recalls of the debut’s genesis. “Sure, if we could do the songs the way we wanted to do them. They agreed.” On a $75 budget and with a single microphone, Siegel engineered the session in Pierce Hall, well known for its grand acoustics, inside DC’s progressive All Souls Unitarian Church. Dickens (singing and string bass) and Gerrard (singing and guitar) showed up experienced, well prepared, and backed by an all-star lineup comprised of mandolinist Grisman, Lamar Grier on banjo, and the legendary Chubby Wise of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys on the fiddle.

The project could have been derailed by the death of Gerrard’s husband Jeremy Foster in a car crash just before recording began, but Gerrard persevered. In 1965, Dickens and Gerrard released an album of hard-driving, traditional bluegrass, Who’s That Knocking?, for Moe Asch’s Folkways Records. “I think this is one of the all-time historic records,” Dickens wrote in a 1996 essay. “To my knowledge, it was the first time that two women sat down and picked out a bunch of songs and had guts enough to stand behind what they picked out and say, ‘We’re not changing anything; you have to do it or else.’”

Dickens and Gerrard recorded their second album, Won’t You Come and Sing for Me?, for Folkways not long after the first, though it sat on the shelf until 1973. Siegel engineered and produced again, this time at Mastertone studio in New York City. The accompanying musicians remained almost the same, but with Billy Baker playing the fiddle instead of Chubby Wise, and Mike Seeger and Fred Weisz contributing to a couple of songs.

By the time Won’t You Come and Sing for Me? came out in 1973, Dickens and Gerrard were entering a new era. They had been touring with the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project, a civil rights–minded organization that promoted interracial cultural exchange in the post–Jim Crow South. These tours politicized Dickens and Gerrard and inspired them to write more of their own songs drawing from injustices they themselves experienced and encountered. Stepping up with impassioned tales of gendered-based double standards, Dickens and Gerrard became unintentional musical spokeswomen for many women’s libbers who connected with their poetic testimonies to the frustrations of living “in a world made by men.”

Though the influential musical couple went their separate ways in 1976, Dickens and Gerrard led accomplished individual music careers and reunited for occasional appearances. Before her passing in 2011, Dickens went on to become a key voice for coal miners’ rights with songs featured in the Academy Award–winning documentary Harlan County, USA and in the labor strike dramatization Matewan. In 2001, she received the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts for her revitalization and reinvention of traditional Appalachian music.

Still active to this day, Gerrard became a critical documentarian of old-time music as the founding editor of The Old Time Herald and through the donation of her extensive archives to the Southern Folklife Collection at UNC. Gerrard earned a Grammy nomination for her 2014 album Follow the Music and has continued to play music in various lineups.

Indeed, Dickens and Gerrard, inducted into the International Bluegrass Hall of Fame in 2017, leave a long legacy of fearless expression that broke down the barriers of the good ol’ boy network in the bluegrass community they helped redefine. “We have had women come up to us all through the years and talk about the first records we made and what an impact it had on their lives,” Dickens wrote in 1996. “I just think it was an eye-opener for a lot of people to hear two women singing together, doing what the men did in bluegrass.”

HAZEL DICKENS AND ALICE GERRARD BIOGRAPHY by Allison Wolfe

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard in the canon of bluegrass music, a historically male-dominated genre in which a sprinkling of women players tended to appear primarily as part of family acts. Self-taught musicians springing from seemingly disparate regional and cultural upbringings, Dickens and Gerrard joined forces in the early 1960s old-time music revival scene in Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, DC, to play the bluegrass—“the young rebel music of its time,” as Dickens put it—that they championed. The tenacious duo cultivated their own raw talents into impactful music careers that spanned about 15 years together and continued, for Dickens, until a month before her death in 2011, and for Gerrard, continues to this day. Feminist by example, they inserted themselves without fanfare in realms unfrequented by women and paved the way for country, folk, and bluegrass luminaries such as Emmylou Harris, the Judds, Alison Krauss, Exene Cervenka, Molly Tuttle, Teresa Trull, Rhiannon Giddens, and even feminist punk bands Le Tigre and (my own band) Bratmobile.

Growing up amidst the working-class struggles she later sang out about, Dickens was born the eighth of 11 children in 1925 in the heart of West Virginia coal country. Her father had been a moonshiner and a banjo picker before becoming a preacher in the Primitive Baptist church, known for its stripped-down approach to worshipping. The raw, a cappella singing style cultivated in the church clearly influenced Dickens’ plaintive, piercing tenor.

Hard times and the hazardous conditions and mechanization of coal mining led to a post–World War II migration to northern industrialized cities. Dickens’ brothers had worked in the mines, and as her family’s opportunities dwindled, they resettled, one by one, in Baltimore. Dickens, who had grown up isolated and sheltered in the mountains, was unprepared for the culture shock of big city life. She found work in the factories and solace in playing traditional music alongside her brothers.

Hailing from a musical family of a different stripe, Gerrard was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1934 to college-educated parents immersed in a classical music community. Her father directed a choir, her mother and aunts performed regularly in a quartet, and Gerrard grew up in a house filled with people playing music for their own entertainment. Her father died young, while rheumatoid arthritis often left her mother bedridden, perhaps leading to Gerrard’s independent and resilient nature.

In the mid-1950s, the wayward Gerrard landed at Antioch College, known for its progressive politics and unconventional educational structure. There she met her future husband, mathematician and musician Jeremy Foster, who introduced her to polymath Harry Smith’s critical Anthology of American Folk Music. It blew Gerrard’s mind. In order to fulfill Antioch’s cooperative education work requirement, the couple relocated to Washington, DC, where their jobs became secondary to their desire to be where music and culture were happening.

Gerrard and Foster dove into the folk revival that was brewing in the Baltimore-Washington area, where many of its urban movers and shakers sought out the authentic, traditional music of Appalachian migrants. Though skeptical of this middle-class curiosity within an environment condescending toward “hillbillies,” Dickens felt validated by the open-minded interest in her culture. The singer and multi-instrumentalist crossed paths and collaborated with prolific musician and ethnomusicologist Mike Seeger (half-brother of activist folk singer Pete Seeger), who worked at a tuberculosis sanatorium where her brother was convalescing.

Through Foster and Seeger, who had been friends since high school, Dickens and Gerrard met within the flourishing house picking-party scene. Dickens, who had already been playing and singing much of her life, became a mentor to Gerrard, who learned the music she loved but hadn’t grown up with by watching and listening. Sharing a passion for the Stanley Brothers and Bill Monroe, Dickens and Gerrard eventually fused their complementary high lonesome and contralto voices into a bold bluegrass duo that became the hit of local house parties and park picnic shows. Recording engineer, producer, and fellow musician Peter Siegel happened upon Hazel and Alice at a house party where they were holding court. Immediately drawn to the young performers’ unique, powerful voices, Siegel approached them about a proper recording.

By 1965, Dickens and Gerrard recorded and released their first album, Who’s That Knocking?, for Moe Asch’s Folkways Records. On a $75 budget and with a single microphone, Siegel engineered the session in Pierce Hall, well known for its grand acoustics, inside DC’s progressive All Souls Unitarian Church. Dickens (vocals and string bass) and Gerrard (vocals and guitar) showed up experienced, well prepared, and backed by an all-star lineup comprised of mandolinist David Grisman, Lamar Grier on banjo, and the legendary Chubby Wise of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys on the fiddle. The project could have been derailed by the death of Gerrard’s husband Foster in a car crash just before recording began. Devastated, with four young children to raise on her own, Gerrard persevered with the support of her tight-knit music community.

Dickens and Gerrard recorded their next album, Won’t You Come and Sing for Me?, for Folkways not long after the first, though it sat on the shelf until 1973. Siegel also engineered and produced the second album, but this time at Mastertone studio in New York City. The session personnel remained almost the same, with the exception of Billy Baker playing the fiddle instead of Chubby Wise, and Mike Seeger and Fred Weisz contributing to a couple of songs.

On both albums, Dickens’ powerful wail soars above Gerrard’s grounding, mid-range sonance. Their bold melodies and nurturing harmonies weave heartbreak, homesickness, and hard times into stories of courage and survival. Impressed by the compatibility of the divergent timbres of their voices, Siegel affirms, “They occupied different sonic spaces and were able to harmonize quite beautifully without getting in each other’s way.”

By the time Won’t You Come and Sing for Me? came out in 1973, Dickens and Gerrard were entering a new era with the release of their album Hazel & Alice in the same year on Rounder Records. They had been touring with the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project, a civil rights–minded organization founded by Bernice Johnson Reagon and Anne Romaine that promoted interracial cultural exchange within the post–Jim Crow South. These tours politicized Dickens and Gerrard and inspired them to write more of their own songs drawing from injustices they themselves experienced and encountered. Stepping up with impassioned tales of gendered double standards, Dickens and Gerrard became unintentional musical spokeswomen for many women’s libbers who connected with their poetic testimonies to the frustrations of living “in a world made by men.”

In honor of the foundational work that set the stage for the bluegrass trailblazers’ momentous careers, Smithsonian Folkways is re-releasing Dickens’ and Gerrard’s first two seminal albums separately on vinyl and combined on CD, including a previously unreleased track, “Childish Love,” from the original New York session. Both albums were previously compiled into a 1996 Smithsonian Folkways CD release, Pioneering Women of Bluegrass (without the track “Weary Lonesome Blues” from the Won’t You Come and Sing for Me? LP).

The repertoire selection in the current Smithsonian Folkways release consists of the duo’s signature takes on mostly traditional songs, with the exception of “Cowboy Jim,” “Gabriel’s Call,” “Difficult Run,” and “Won’t You Come and Sing for Me,” which were written by Dickens, Gerrard, or their musical collaborators. A standout, “The One I Love Is Gone” was gifted to Dickens and Gerrard by the father of bluegrass, Bill Monroe, who was also a friend and fan. Dickens, who wasn’t religious, wrote “Won’t You Come and Sing for Me,” the title track of the second album, as a tribute to the humble church community she came from. “Coal Miner’s Blues” depicts working-class struggles Dickens knew all too well, while her rendition of the classic “Long Black Veil” exemplifies what longtime collaborator Dudley Connell calls Dickens’ signature “laser tenor.”

Though the influential musical couple went their separate ways in 1976, Dickens and Gerrard led accomplished individual music careers and reunited many years later for occasional appearances. Dickens went on to become a key voice for coal miners’ rights with hard-hitting songs featured in the Academy Award–winning documentary Harlan County, USA and in the labor strike dramatization Matewan. In 2001, Dickens received the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts for her revitalization and reinvention of traditional Appalachian music. Gerrard became a critical documentarian of old-time music as the founding editor of The Old Time Herald and through the donation of her extensive archives to the Southern Folklife Collection at UNC. Gerrard earned a Grammy nomination for her 2014 album Follow the Music and has continued to play music in various lineups to this day. Indeed, Dickens and Gerrard, inducted into the International Bluegrass Hall of Fame in 2017, leave a long legacy of fearless expression that broke down the barriers of the good ol’ boy network in the bluegrass community they helped redefine.

Photo Credits:

(1) Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard in the studio, 1960s (by John Cohen);

(2) Alice Gerrard (by Irene Young);

(3)-(5) Hazel Dickens & Alice Gerrard LP Covers

(by Smithsonian Folkways).