The Rudolstadt Festival, Germany's largest festival for roots, folk and world music, focuses on Persian music in 2019. The rich musical tradition of Iran has so far been perceived as one-sided, says program director Bernhard Hanneken: "Persia is one of the oldest cultural regions in the world, which has also significantly influenced the European musical life. We are especially familiar with classical Persian music, however, we do not know much about folk music in the regions and about the current music scene. The festival wants to try to reflect all these tendencies in the coming year."

The music of Iran encompasses music that is produced by Iranian artists. In addition to the traditional folk and classical genres, it also includes pop and internationally-celebrated styles such as jazz, rock, and hip hop.

Iranian music influenced other cultures in West Asia, building up much of the musical terminology of the neighboring Turkic and Arabic cultures, and reached India through the 16th-century Persianate Mughal Empire, whose court promoted new musical forms by bringing Iranian musicians

Music in Iran, as evidenced by the "pre-Iranian" archaeological records of Elam, the oldest civilization in southwestern Iran, dates back thousands of years. Iran is apparently the birthplace of the earliest complex instruments, which date back to the third millennium BC. A number of trumpets made of silver, gold, and copper were found in eastern Iran that are attributed to the Oxus civilization and date back between 2200 and 1750 BC. The use of both vertical and horizontal angular harps have been documented at the archaeological sites of Madaktu (650 BC) and Kul-e Fara (900–600 BC), with the largest collection of Elamite instruments documented at Kul-e Fara. Multiple depictions of horizontal harps were also sculpted in Assyrian palaces, dating back between 865 and 650 BC.

Not much is known on the music scene of the classical Iranian empires of the Medes, the Achaemenids, and the Parthians, other than a few archaeological remains and some notations from the writings of Greek historians. According to Herodotus, the magi, who were a priestly caste in ancient Iran, accompanied their sacrifice rituals with singing. Athenaeus of Naucratis, in his Deipnosophistae, mentions a court singer who had sung a warning to the king of the Median Empire of the plans of Cyrus the Great, who would later establish the Achaemenid dynasty on the throne. Athenaeus also points out to the capture of singing girls at the court of the last Achaemenid king Darius III (336–330 BC) by Macedonian general Parmenion. Xenophon's Cyropaedia also mentions a great number of singing women at the court of the Achaemenid Empire. Under the Parthian Empire, the gōsān (Parthian for "minstrel") had a prominent role in the society. They performed for their audiences at royal courts and in public theaters. According to Plutarch's Life of Crassus (32.3), they praised their national heroes and ridiculed their Roman rivals. Likewise, Strabo's Geographica reports that the Parthian youth were taught songs about "the deeds both of the gods and of the noblest men". Parthian songs were later absorbed into the Iranian national epic of Šāhnāme, composed by 10th-century Persian poet Ferdowsi. Šāhnāme itself was based on Xwadāynāmag, an earlier Middle Persian work that is now lost. It is also mentioned in Plutarch's Life of Crassus (23.7) that the Parthians used drums to prepare for battle.

Under the reign of the Sasanians, the Middle Persian term huniyāgar was used to refer to a minstrel. The history of Sasanian music is better documented than the earlier periods, and is especially more evident in Avestan texts. The recitation of the Sasanian Avestan text of Vendidād has been connected to the Oxus trumpet. The Zoroastrian paradise itself was known as the "House of Song" (garōdmān in Middle Persian), "where music induced perpetual joy". Musical instruments were not accompanied with formal Zoroastrian worship, but they were used in the festivals. Sasanian musical scenes are depicted especially on silver vessels and some wall reliefs.

The reign of Sasanian ruler Khosrow II is regarded as a "golden age" for Iranian music. He is shown among his musicians on a large relief at the archaeological site of Taq-e Bostan, holding a bow and arrows himself and standing in a boat amidst a group of harpists. The relief depicts two boats that are shown at "two successive moments within the same panel". The court of Khosrow II hosted a number of prominent musicians, including Azad, Bamshad, Barbad, Nagisa, Ramtin, and Sarkash. Among these attested names, Barbad is remembered in many documents and has been named as remarkably high skilled. He was a poet-musician who performed on occasions such as state banquets and the festivals of Nowruz and Mehrgan. He may have invented the lute and the musical tradition that was to transform into the forms of dastgah and maqam. He has been credited to have organized a musical system consisting of seven "royal modes" (xosrovāni), 30 derived modes (navā), and 360 melodies (dastān). These numbers are in accordance with the number of days in a week, month, and year in the Sasanian calendar. The theories these modal systems were based on are not known. However, the writers of later periods have left a list of these modes and melodies. These names include some epic forms, such as Kin-e Iraj ("Vengeance of Iraj"), Kin-e Siāvaš ("Vengeance of Siavash"), and Taxt-e Ardašir ("Throne of Ardashir"), and some connected with the glories of the Sasanian royal court, such as Bāğ-e Širin ("Garden of Shirin"), Bāğ-e Šahryār ("Garden of the Sovereign"), and Haft Ganj ("Seven Treasures"). There are also some of a descriptive nature, like Rowšan Čerāğ ("Bright Light").

Iran's academic classical music, in addition to preserving melody types that are often attributed to Sasanian musicians, is based on the theories of sonic aesthetics as expounded by the likes of Iranian musical theorists in the early centuries of after the Muslim conquest of the Sasanian Empire, most notably Avicenna, Farabi, Qotb-ed-Din Shirazi, and Safi-ed-Din Urmawi.

Ebrahim Mawseli and his son Eshaq Mawseli were prominent musicians of Iranian origin who lived under reign of the third Arab caliphate. Zaryab of Baghdad, a student of Eshaq, is credited with having had left remarkable influences on Spain's classical Andalusian music.

Following the revival of Iranian traditions through the arrival of a number of Muslim Iranian dynasties, music became once again "one of the signs of rule". 9th-century Persian poet Rudaki, who lived under the reign of the Samanids, was also a musician and composed songs to his own poems. At the court of the Persianate Ghaznavids, who ruled Iran between 977 and 1186, 10th-century Persian poet Farrokhi Sistani also composed songs, together with a singer named Andalib and a tanbur player named Buqi. A lute player named Mohammad Barbati and a songstress named Setti Zarrin-kamar also entertained the Ghaznavid rulers at their court.

In the post-medieval era, musical performances continued to be observed and promoted through especially princely courts, Sufi orders, and modernizing social forces. Under the reign of the 19th-century Qajar dynasty, Iranian music was renewed through the development of classical melody types (radif), that is the basic repertoire of Iran's classical music, and the introduction of modern technologies and principles that were introduced from the West. Mirza Abdollah, a prominent tar and setar master and one of the most respected musicians of the court of the late Qajar period, is considered a major influence on the teaching of classical Iranian music in Iran's contemporary conservatories and universities. Radif, the repertoire that he developed in the 19th century, is the oldest documented version of the seven dastgah system, and is regarded as a rearrangement of the older 12 maqam system.

Ali-Naqi Vaziri, a respected player of numerous Iranian and western instruments who studied western musical theory and composition in Europe, was one of the most prominent and influential musicians of the late Qajar and early Pahlavi periods. He established a private music school in 1924, where he also created a school orchestra composed of his students, formed by a combination of the tar and some western instruments. Vaziri then founded an association named Music Club (Kolub-e Musiqi), formed by a number of progressive-minded writers and scholars, where the school orchestra performed concerts that were conducted by himself. He was an extraordinary figure among the Iranian musicians of the 20th century, and his primary goal was to provide music for ordinary citizens through a public arena. The Tehran Symphony Orchestra (Orkestr-e Samfoni-ye Tehrān) was founded by Gholamhossein Minbashian in 1933. It was reformed by Parviz Mahmoud in 1946, and is currently the oldest and largest symphony orchestra in Iran. Later, Ruhollah Khaleqi, a student of Vaziri, established the Society for National Music (Anjoman-e Musiqi-ye Melli) in 1949. Numerous musical compositions were produced within the parameters of classical Iranian modes, and many involved western musical harmonies. Iranian folkloric songs and poems of both classical and contemporary Iranian poets were incorporated for the arrangement of orchestral pieces that would bear the new influences.

Prior to the 1950s, Iran's music industry was dominated by classical artists. New western influences were introduced into the popular music of Iran by the 1950s, with electric guitar and other imported characteristics accompanying the indigenous instruments and forms, and the popular music developed by the contributions of artists such as Viguen, who was known as the "Sultan" of Iranian pop and jazz music. Viguen was one of Iran's first musicians to perform with a guitar.

Following the 1979 Revolution, the music industry of Iran went under a strict supervision, and pop music was prohibited for almost two decades. Women got banned from singing as soloists for male audiences. In the 1990s, the new regime began to produce and promote pop music in a new standardized framework, in order to compete with the abroad and unsanctioned sources of Iranian music. Under the presidency of Reformist Khatami, as a result of easing cultural restrictions within Iran, a number of new pop singers emerged from within the country. Since the new administration took office, the Ministry of Ershad adopted a different policy, mainly to make it easier to monitor the industry. The newly adopted policy included loosening restrictions for a small number of artists, while tightening it for the rest. However, the number of album releases increased.

The emergence of Iranian hip hop in the 2000s also resulted in major movements and influences in the music of Iran.

The classical music of Iran consists of melody types developed through the country's classical and medieval eras. Dastgah, a musical mode in Iran's classical music, despite its popularity, has always been the preserve of the elite. The influence of dastgah is seen as the reservoir of authenticity that other forms of musical genres derive melodic and performance inspiration from.

Iran's folk, ceremonial, and popular songs might be considered "vernacular" in the sense that they are known and appreciated by a major part of the society (as opposed to the art music, which caters for the most part to more elite social classes). The variance of the folk music of Iran has often been stressed, in accordance to the cultural diversity of the country's local and ethnic groups.

Iranian folk songs are categorized in various themes, including those of historical, social, religious, and nostalgic contexts. There are also folk songs that apply to particular occasions, such as weddings and harvests, as well as lullabies, children's songs, and riddles.

There are several traditional specialists of folk music in Iran. Professional folk instrumentalists and vocalists perform at formal events such as weddings. Storytellers (naqqāl; gōsān) would recite epic poetry, such as that of the Šāhnāme, using traditional melodic forms, interspersing with spoken commentary, which is a practice found also in Central Asian and Balkan traditions. The bakshy (baxši), wandering minstrels who play the dotar, entertain their audiences at social gatherings with romantic ballads about warriors and warlords. There are also lament singers (rowze-xān), who recite verses that would commemorate the martyrdom of religious figures.

Iranian singers of both classical and folk music may improvise the lyric and the melody within the proper musical mode. Many Iranian folk songs have the potential of being adapted into major or minor tonalities, and therefore, a number of Iranian folk songs were arranged for orchestral accompaniment.

Many of Iran's old folkloric songs were revitalized through a project developed by the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, a cultural and educational institute that was founded under the patronage of Iran's former empress Farah Pahlavi in 1965. They were produced in a collection of quality recordings, performed by professional vocalists such as Pari Zanganeh, Monir Vakili, and Minu Javan, and were highly influential in Iran's both folk and pop music productions.

Iran's symphonic music, as observed in the modern times, was developed by the late Qajar and early Pahlavi periods. In addition to instrumental compositions, some of Iran's symphonic pieces are based on the country's folk songs, and some are based on poetry of both classical and contemporary Iranian poets.

Symphonische Dichtungen aus Persien ("Symphonic Poems from Persia"), a collection of Persian symphonic works, was performed by the German Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra and conducted by Iranian conductor Ali Rahbari in 1980.

Loris Tjeknavorian, an acclaimed Iranian Armenian composer and conductor, composed Rostam and Sohrab, an opera with Persian libretto that is based on the tragedy of Rostam and Sohrab from Iran's long epic poem Šāhnāme, in over two decades. It was first performed by the Tehran Symphony Orchestra at Tehran's Roudaki Hall in December 2003.

In 2005, the Persepolis Orchestra (Melal Orchestra) played a piece that dates back 3000 years. The notes of this piece, which were discovered among some ancient inscriptions, were deciphered by archaeologists and are believed to have belonged to the Sumerians and the ancient Greeks. Renowned Iranian musician Peyman Soltani conducted the orchestra.

Following the emergence of radio, under the reign of the Qajar dynasty, a form of popular music was formed and began to develop in Iran. Later, the arrival of new western influences, such as the use of the guitar and other western instruments, marked a turning point in Iran's popular music by the 1950s. Iranian pop music is commonly performed by vocalists who are accompanied with elaborate ensembles, often using a combination of both indigenous Iranian and European instruments.

The pop music of Iran is largely promoted through mass media, but it experienced some decade of prohibition after the 1979 Revolution. Public performances were also banned, but they have been occasionally permitted since 1990. The pop music of Iranian diasporan communities has also been significant.

Jazz music was introduced into Iran's popular music by the emergence of artists such as Viguen, who was known as Iran's "Sultan of Jazz". Viguen's first song, Moonlight, which was released in 1954, was an instant hit on the radio and is considered highly influential.

Indigenous Iranian elements, such as classical musical forms and poetry, have also been incorporated into Iranian jazz. Rana Farhan, an Iranian jazz and blues singer living in New York, combines classical Persian poetry with modern jazz and blues. Her best-known work, Drunk With Love, is based on a poem by prominent 13th-century Persian poet Rumi. Jazz and blues artists who work in post-revolutionary Iran have also gained popularity.

Rock music was introduced into Iran's popular music by the 1960s, together with the emergence of other Western European and American musical genres. It soon became popular among the young generation, especially at the nightclubs of Tehran. In post-revolutionary Iran, many rock music artists are not officially sanctioned and have to rely on the Internet and underground scenes.

In 2008, power metal band Angband signed with German record label Pure Steel Records as the first Iranian metal band to release internationally through a European label. They had collaborations with well-known producer Achim Köhler.

Iranian hip hop emerged by the 2000s, from the country's capital city, Tehran. It started with underground artists recording mixtapes influenced by the American hip hop culture, and was later combined with elements from the indigenous Iranian musical forms.

Persian traditional music or Iranian traditional music, also known as Persian classical music or Iranian classical music, refers to the classical music of Iran (also known as Persia). It consists of characteristics developed through the country's classical, medieval, and contemporary eras.

Due to the exchange of musical science throughout history, many of Iran's classical melodies and modes are related to those of its neighboring cultures.

Iran's classical art music continues to function as a spiritual tool, as it has throughout history, and much less of a recreational activity. It belongs for the most part to the social elite, as opposed to the folkloric and popular music, in which the society as a whole participates. However, the parameters of Iran's classical music have also been incorporated into folk and pop music compositions.

The history of musical development in Iran dates back thousands of years. Archaeological records attributed to "pre-Iranian" civilizations, such as those of Elam in the southwest and of Oxus in the northeast, demonstrate musical traditions in the prehistoric times.

Little is known about the music of the classical Iranian empires of the Medes, the Achaemenids, and the Parthians. However, an elaborate musical scene is revealed through various fragmentary documents, including those that were observed at the court and in public theaters and those that accompanied religious rituals and battle preparations. Jamshid, a king in Iranian mythology, is credited with the "invention" of music.

The history of Sasanian music is better documented than the earlier periods, and the names of various instruments and court musicians from the reign of the Sasanians have been attested. Under the Sasanian rule, modal music was developed by a highy-celebrated poet-musician of the court named Barbad, who is remembered in many documents. He may have invented the lute and the musical tradition that was to transform into the forms of dastgah and maqam. He has been credited to have organized a musical system consisting of seven "royal modes" (xosrovāni), 30 derived modes (navā), and 360 melodies (dāstān).

Iran's academic classical music, in addition to preserving melody types attributed to Sasanian musicians, is based on the theories of sonic aesthetics as expounded by the likes of Iranian musical theorists in the early centuries of after the Muslim conquest of the Sasanian Empire, most notably Avicenna, Farabi, Qotb-ed-Din Shirazi, and Safi-ed-Din Urmawi. It is also linked directly to the music of the 16th–18th-century Safavid Empire. Under the reign of the 19th-century Qajar dynasty, the classical melody types were developed, alongside the introduction of modern technologies and principles from the West. Mirza Abdollah, a prominent tar and setar master and one of the most respected musicians of the court of the late Qajar period, is considered a major influence on the teaching of classical Iranian music in Iran's contemporary conservatories and universities. Radif, the repertoire that he developed in the 19th century, is the oldest documented version of the seven dastgah system, and is regarded as a rearrangement of the older 12 maqam system. During the late Qajar and the early Pahlavi periods, numerous musical compositions were produced within the parameters of classical Iranian modes, and many involved western musical harmonies.

The introduction and popularity of western musical influences in the early contemporary era was criticized by traditionalists, who felt that traditional music was becoming endangered. It was prior to the 1950s that Iran's music industry was dominated by classical musicians. In 1968, Dariush Safvat and Nur-Ali Borumand helped form an institution called the Center for Preservation and Propagation of Iranian Music, with the help of Reza Ghotbi, director of the National Iranian Radio and Television, an act that is credited with saving traditional music in the 1970s.

The "Radif of Iranian music" was officially inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009, described as "the traditional repertoire of the classical music of Iran".

Iran's classical art music relies on both improvisation and composition, and is based on a series of modal scales and tunes. Compositions can vary immensely from start to finish, usually alternating between low, contemplative pieces and athletic displays of musicianship called tahrir. The common repertoire consists of more than 200 short melodic motions (guše), which are classified into seven modes (dastgāh). Two of these modes have secondary modes branching from them that are called āvāz. This whole body is called radif, of which there are several versions, each in accordance to the teachings of a particular master (ostād).

By the end of the Safavid Empire, more complex musical movements in 10, 14, and 16 beats stopped being performed. In the early Qajar era, the rhythmic cycles (osul) were replaced by a meter based on the qazal, and the maqam system of classification was reconstructed into the radif system. Today, rhythmic pieces are performed in beats of 2 to 7, with some exceptions. The reng are always in a 6/8 time frame.

A typical Iranian classical performance consists of five parts, namely pišdarāmad ("prelude"; a composed metric piece), čahārmezrāb (a fast, metric piece with a repeated rhythmic pattern), āvāz (the improvised central piece), tasnif (a composed metric song of classical poetry), and reng (a rhythmic closing composition). A performance forms a sort of suite. Unconventionally, these parts may be varied or omitted.

Iran's classical art music is vocal based, and the vocalist plays a crucial role, as he or she decides what mood to express and which dastgah relates to that mood. In many cases, the vocalist is also responsible for choosing the lyrics. If the performance requires a singer, the singer is accompanied by at least one wind or string instrument, and at least one type of percussion. There could be an ensemble of instruments, though the primary vocalist must maintain his or her role. In some tasnif songs, the musicians may accompany the singer by singing along several verses.

The incorporation of religious texts as lyrics has largely been replaced by the works of medieval Sufi poets, especially Hafez and Rumi.

Indigenous Iranian musical instruments used in the traditional music include string instruments such as the chang (harp), qanun, santur, rud (oud, barbat), tar, dotar, setar, tanbur, and kamanche, wind instruments such as the sorna (zurna, karna), ney, and neyanban, and percussion instruments such as the tompak, kus, daf (dayere), naqare, and dohol.

Some instruments, such as the sorna, neyanban, dohol, and naqare, are usually not used in the classical repertoire, but are used in the folk music. Up until the middle of the Safavid Empire, the chang was an important part of Iranian music. It was then replaced by the qanun (zither), and later by the western piano. The tar functions as the primary string instrument in a performance. The setar is especially common among Sufi musicians. The western violin is also used, with an alternative tuning preferred by Iranian musicians. The ghaychak, that is a type of fiddle, is being re-introduced to the classical music after many years of exclusion.

Iranian folk music refers to the folk music transmitted through generations among the people of Iran, often consisting of tunes that exist in numerous variants.

The variance of the folk music of Iran has often been stressed, in accordance to the cultural diversity of the country's ethnic and regional groups. Musical influences from Iran, such as the ancient folkloric chants for group dances and spells directed at natural elements and cataclysms, have also been observed in the Caucasus.

Iran's folk, ceremonial, and popular songs might be considered "vernacular", in the sense that they are known and appreciated by a major part of the society, as opposed to the country's art music, which belongs for the most part to the intellectuals.

Folkloric items, such as folk-tales, riddles, songs, and everyday-life narratives, were collected through the discovery and translation of the Avesta, that is a collection of ancient Iranian religious texts. In classical Iran, minstrels (gōsān; huniyāgar) had a prominent role in the society. They performed for their audiences at royal courts and in public theaters. Ancient Greek historian Plutarch, in his Life of Crassus (32.3), reports that they praised their national heroes and ridiculed their Roman rivals. Likewise, Strabo's Geographica reports that the Parthian youth were taught songs about "the deeds both of the gods and of the noblest men".

The modal concepts in Iranian folk music are linked to those of the country's classical music. Many of Iran's folk songs have the potential of being adapted into major or minor tonalities, and Iranian singers of both classical and folk music may improvise the lyric and the melody within the appropriate musical mode. Experiments and influences from Iran's folk music have been incorporated into the musical appearance of tasnif, that is a type of vocal composition in Iranian classical music. Composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries used the folk music of their native countries as a source of inspiration for their compositions. Iranian folk songs were incorporated into musical compositions that were produced within the parameters of classical Iranian modes, combined with western musical harmonies. Elements deriving from Iran's folk and classical music have been combined and used also in the pop music.

Iranian folk music is categorized in various themes, and includes historical, social, religious, and nostalgic contexts. There are folk songs that apply to particular occasions, such as weddings and harvests, as well as lullabies, children's songs, and riddles. The poetic meter of do-beyti ("two-couplet"), often sung in the Iranian vocal mode of āvāz-e dašti, is closely associated with Iranian folk tunes.

Ruhowzi, a musical comedy in Iran's traditional theater, involves loose paraphrases of stories from Iranian folklore and classical literature that are already known to the audience. The stories contain funny remarks that are improvised and indicate social and cultural concepts. Traditionally, ruhowzi was performed on stages made of boards that were covered with rugs and were put on a small pool (howz) in the courtyard.

Musical instruments of various sorts are used in Iran's traditional music, some of which belong to specific groups. Three types of instruments are common to all parts of the country, namely sorna (karnay, zurna), ney (flute), and a doubleheader drum called dohol.

Iranian folk musicians usually learn their art from their families. There are several types of traditional specialists of folk music in Iran, some of whom belong to specific ethnic and regional groups. Professional folk instrumentalists and vocalists (motreb) perform at formal ceremonial events such as weddings. Storytellers (naqqāl; gōsān) would recite epic poetry, such as that of Iran's long epic poem of Šāhnāme, using traditional melodic forms that are interspersed with spoken commentary, which is a practice found also in Central Asian and Balkan musical traditions. The bakshy (baxši), wandering minstrels who play the dotar, entertain their audiences at social gatherings with romantic ballads about warriors and warlords. There are also lament singers (rowze-xān), who recite verses that would commemorate the martyrdom of religious figures.

Many of Iran's old folkloric songs were revitalized through a project developed by the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, a cultural and educational institute that was founded under the patronage of Iran's former empress Farah Pahlavi in 1965. They were produced in a collection of quality recordings, performed by professional Iranian vocalists such as Pari Zanganeh, Monir Vakili, and Minu Javan, and were remarkably influential in Iran's both folk and pop music productions.

In 1997, the American jazz fusion ensemble Pat Metheny Group released an album named Imaginary Day that contained inspirations from the folk music of Iran. The album was awarded a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Jazz Album in 1999.

In 2006, prominent musicians Hossein Alizâdeh and Djivan Gasparyan produced a collaborative album of traditional Iranian and Armenian songs named Endless Vision, originally recorded at the Niavaran Palace of Tehran. It was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Traditional World Music Album in 2007.

In 2007, Baluch folklore vocalist Mulla Kamal Khan was awarded at a ceremony by grand master of traditional Iranian music Mohammad-Reza Shajarian for his contribution to the folk music of Iran's southeastern region of Baluchestan.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

Date: February 2019.

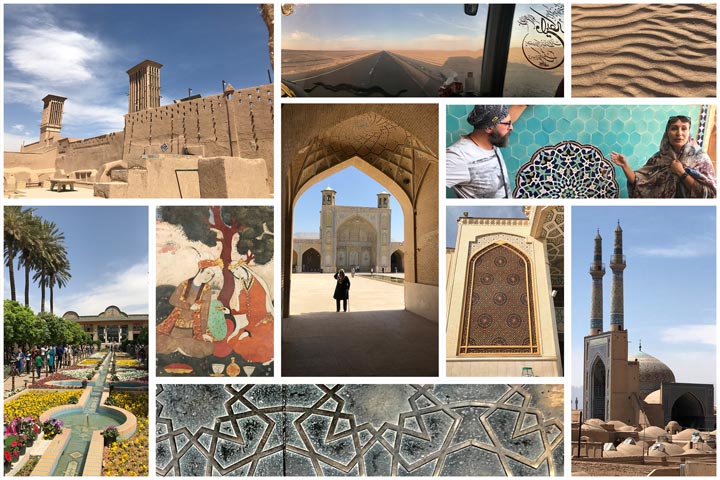

Photo Credits:

(1)-(2) Impressions from Iran,

(3),(5) Rudolstadt-Festival,

(6) Mehdi Rajabian,

(7) Mahsa Vahdat,

(8)-(10) Mehdi & Adib Rostami,

(11) Mamak Khadem Ensemble,

(12) Mohammad Reza Mortazavi,

(13) Liraz,

(14) Ooldouz Pouri,

(15) Sara Najafi (No Land's Song),

(16) Saeid Shanbehzadeh,

(17) Setar

(unknown/website);

(4) Cymin Samawatie

(by Karsten Rube).