FolkWorld article by Susanne Kalweit:

"I WOULDN'T CHANGE A THING!"

40 years of Iain MacKintosh

I can't believe it's thirty years since three of us teamed up

I can't believe it's thirty years since three of us teamed up

Won a folk group competition - I've still got that silver cup

In a basement club in Bath Street for me it did begin

Songs from Archie, Alex Campbell, Josh MacRae and Matt McGinn

I played a bingo hall in Wishaw, a church hall in Polmadie

The more I sang the more I thought, Aye, that's the life for me

I don't remember where it was, but someone paid us once

Between you and me - I havnae done an honest day's work since

An audition at the Ashfield Club, with three songs up our sleeves

The boy said, Lads, don't waste my time, can ye no dae some Jim Reeves?

Then I got my first TV show from the Elbow Room in Fife

Sometimes I think that Gordon Smith (the producer!) was the man who changed my life

Time went on and line-ups changed, one group became another

Jackie, Gavin, Bobby, Tam - I loved them like my brothers

Then one day I thought I'd like to try it on my own

And a whole new world just opened up when I stood up there alone

It didnae take me long to find the songs I liked to do

Mostly songs by other folk, though I did write one or two

I sang some Harry Chapin songs, somehow they seemed to suit

And the Glasgow songs by Adam to remind me of my roots

I learned a lot from Hamish too, not just how to drink

There's much more to the big man than a lot of people think

He can mickey mouse the public bar or captivate with blues

Takes three men to fill his trousers - but no one fills his shoes

Some other special friends, of course, they know how I feel

Some other special friends, of course, they know how I feel

There's Allan Taylor, Alan Reid, 'Cecil B.' McNeill

Arthur Johnstone, Rod from Denmark, and the Sands from Ireland too

Jesus - this verse was a big mistake, I can't name all of you

Some virtuoso players - think of Aly, think of Phil

As we sometimes say in Glasgow - that music's pure dead brill

A couple of us made it big - Billy, Babs got rich

Some of us just made it small - Danny, me, and Tich

My family were wonderful, my daughters and my wife

They knew how much I loved this job and enjoyed the travelling life

We smiled through the good times, and they helped me through the rough

Though tempted, they never once said, Take your banjo and piss off

There's never a dull moment now, the tours come rolling in

Baltimore to Bielefeld, Bermuda tae Berlin

No, I can't believe it's thirty years since I began to sing

But if I had to do it all again, I wouldnae change a thing

This musical autobiography in five verses is one of the best-loved

items in Iain MacKintosh's repertoire. He claims to have written it

'within half an hour' when he turned sixty - to cheer himself up, he

says, and to remind himself of all the good things his life as a

travelling folksinger has brought him. (How just like him to maintain

a discreet silence on the downsides!)

This musical autobiography in five verses is one of the best-loved

items in Iain MacKintosh's repertoire. He claims to have written it

'within half an hour' when he turned sixty - to cheer himself up, he

says, and to remind himself of all the good things his life as a

travelling folksinger has brought him. (How just like him to maintain

a discreet silence on the downsides!)

'I Wouldn't Change A Thing' is not only a very personal account of

Iain's forty-year career. It also says a lot about the man whose most

conspicuous character trait is his inconspicuousness. A rave review in

a German newspaper started with the words: 'When he came in you could

have taken him for the janitor ...' Simplicity, authenticity and a

capacity for self-mockery have made him a favourite with his

audiences. In November 1999 he announced - inconspicuously - that he

was going to retire from touring.

Even though he started learning to play the highland pipes at the age

of seven, and played in a prize-winning pipe band for years, a musical

career was not on the cards from the start. The war, which hit his

native Glasgow hard, and his mother's death when he was twelve were

formative experiences of his childhood. From 1944, his formidable

grandmother brought him and his three sisters up. The boy learned a

proper trade - watchmaker and goldsmith - and went to work in his

father's firm.

He prefers not to remember his military service; however, it was here

that he was taught his first riffs on the guitar. In the late Fifties

he went to a Pete Seeger concert in Glasgow. The down-to-earth,

American banjo player who would even cut wood on stage if it served

his music made such a tremendous impression on Iain that he went and

bought a banjo. He had found his instrument. He joined the emerging

Scottish folk scene and discovered there were models to be found

nearer home: Alex Campbell who introduced Europe to British folk

music, Josh MacRae who got the first folk song into the charts with

'Messing About on the River', and that writer of both humorous and

overtly political songs, Matt McGinn.

He prefers not to remember his military service; however, it was here

that he was taught his first riffs on the guitar. In the late Fifties

he went to a Pete Seeger concert in Glasgow. The down-to-earth,

American banjo player who would even cut wood on stage if it served

his music made such a tremendous impression on Iain that he went and

bought a banjo. He had found his instrument. He joined the emerging

Scottish folk scene and discovered there were models to be found

nearer home: Alex Campbell who introduced Europe to British folk

music, Josh MacRae who got the first folk song into the charts with

'Messing About on the River', and that writer of both humorous and

overtly political songs, Matt McGinn.

Unlike fellow musicians like Hamish Imlach or Archie Fisher and his

sisters Cilla and Ray, who were born into the British folk revival and

started playing more or less professionally while still in their

teens, Iain was in his late twenties when he formed his first band. In

1960 'The Islanders' emerged. They were, or so Iain says, 'not very

good, but successful'. These things happen. If you know, however, that

he is his own severest critic, this harsh judgment may be taken with a

grain of salt.

For ten years, Iain played in different bands; 'The Islanders' were

followed by 'The Skerries' and 'The Other Half'. At the same time, he

made a name for himself as session musician on other people's albums,

among them 'Gaberlunzie' and Hamish Imlach, who would later write, in

his introduction to Iain's first solo album: 'I have heard Iain in

various groups over many years. They have always been good groups,

although I did not at first understand why. Iain was always in the

background, introspective, and the audience would not notice him

playing really sensitive music ... When he started singing and playing

himself, I was first amazed, then jealous, and then sat back and

enjoyed listening.'

After long 'apprenticeship', in 1970 Iain decided to leave the

background and earn his money as a solo artist. Economic change in

Scotland may have contributed to the decision to close down the

parental business which Iain had been running with his wife Sadie from

1960. However, it was probably the growing demand on his time by his

second job that made a decision between the two necessary. For his

wife and his two daughters life with a constantly absent father can't

have been exactly easy. From 1973, he was increasingly touring Germany

and other European countries, and also the United States - often nine

months out of twelve. Sadie kept the home running. She doesn't speak

about what this meant for her. Daughters Isla and Fiona do admit to

occasionally being embarrassed by having to give their father's job as

'folksinger' in school. Isla preferred to state he was a plumber

instead, while Fiona, if she knew her father was appearing on TV, e.g.

in the series 'A Better Class of Folk' hosted by Dominic Behan, would

steer her schoolfellows to a café that didn't have a set.

After long 'apprenticeship', in 1970 Iain decided to leave the

background and earn his money as a solo artist. Economic change in

Scotland may have contributed to the decision to close down the

parental business which Iain had been running with his wife Sadie from

1960. However, it was probably the growing demand on his time by his

second job that made a decision between the two necessary. For his

wife and his two daughters life with a constantly absent father can't

have been exactly easy. From 1973, he was increasingly touring Germany

and other European countries, and also the United States - often nine

months out of twelve. Sadie kept the home running. She doesn't speak

about what this meant for her. Daughters Isla and Fiona do admit to

occasionally being embarrassed by having to give their father's job as

'folksinger' in school. Isla preferred to state he was a plumber

instead, while Fiona, if she knew her father was appearing on TV, e.g.

in the series 'A Better Class of Folk' hosted by Dominic Behan, would

steer her schoolfellows to a café that didn't have a set.

As a solo artist, Iain has always been political, though he is no

agitator. The songs he likes best are the ones with a subtle political

message. This may account for his passion for story songs. He doesn't

care where he picks them up - whether at home in Glasgow, from Adam

McNaughtan who not only wrote the hilarious 'Oor Hamlet' but also

'Blood Upon the Grass', on the murder of Victor Jara, or in the States

from where he has brought back and 'scottified' many of his best-known

songs. He has a particular liking for Harry Chapin, the late American

singer-songwriter and co-founder of World Hunger. Whenever Iain sang a

particularly impressive or moving new song you could almost be sure

that the author was Harry Chapin. After Harry's premature death, his

wife had a tape of songs he left behind sent to Iain MacKintosh. She

didn't know Iain but she had heard that he was keeping Harry's name

and songs alive.

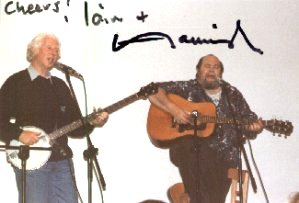

Iain's professional work with the sadly missed Hamish Imlach turned

into a lifelong friendship, although - or perhaps because - this was a

meeting of absolute opposites: On the one hand the spare, quiet,

self-contained aesthete, careful with money, abhorring cigarettes and

hardly ever seen drinking; on the other hand the large, generous

bohémien who would freely admit his addiction to good food, alcohol,

nicotine and other people's company. As in life, this contrast had its

effect on stage when Iain and Hamish started performing as a duo.

Iain's professional work with the sadly missed Hamish Imlach turned

into a lifelong friendship, although - or perhaps because - this was a

meeting of absolute opposites: On the one hand the spare, quiet,

self-contained aesthete, careful with money, abhorring cigarettes and

hardly ever seen drinking; on the other hand the large, generous

bohémien who would freely admit his addiction to good food, alcohol,

nicotine and other people's company. As in life, this contrast had its

effect on stage when Iain and Hamish started performing as a duo.

Unlike Hamish, Iain has never been a focal point for the folk scene.

He is too private for that, and is too little interested in some of

the accompanying features of the scene. Also, he soon discovered songs

that could be called folk songs only by virtue of his presentation. In

spite of all this he enjoys the friendship of many fellow musicians,

whether they be stars like Allan Taylor, Alan Reid, Brian McNeill or

the Sands Family, or people like Arthur Johnstone who, as the

long-standing 'engine room' of Glasgow's Star Folk Club, helped to

keep the music alive at grassroots level. Incidentally, the Star Club

voted Iain 'folksinger of the year' several times in his career.

For some fellow musicians, Iain has become a kind of father figure by

virtue of his age and experience. Who would have guessed that among

the musical influences on 'Wolfstone' must be counted 'Uncle Iain',

who many a night played the sons of his good friend Peter Eaglesham to

sleep with his banjo and thus helped foster their interest in the

music. However, Iain also tells the story against himself of how, many

years ago, he tried in vain to convince a fifteen-year-old who had run

away from school in order to join his brother's band, of the

advantages of getting an education. Runaway Phil Cunningham went on to

become Scotland's accordion wizard (and one of Iain's musical heroes)

and probably never once missed his unfinished education.

However, in folk music, as everywhere, you don't become a star simply

by being a virtuoso player. You also need luck, a sense of showmanship

off as well as on stage, and perhaps more readiness to adapt to

audiences' expectations than Iain was willing to bring to his job.

That's why he never got his big break, unlike, for instance,

long-haired stand-up comic Billy Connolly who started out as a

folksinger with 'The Humblebums' at roughly the same time as Iain.

There is no indication, however, that Iain envies him his material

success and his world-wide popularity.

However, in folk music, as everywhere, you don't become a star simply

by being a virtuoso player. You also need luck, a sense of showmanship

off as well as on stage, and perhaps more readiness to adapt to

audiences' expectations than Iain was willing to bring to his job.

That's why he never got his big break, unlike, for instance,

long-haired stand-up comic Billy Connolly who started out as a

folksinger with 'The Humblebums' at roughly the same time as Iain.

There is no indication, however, that Iain envies him his material

success and his world-wide popularity.

Iain has got his own highlights: He feels at home with what he is

singing and doing because he knows he is doing it well and it fits his

character. Although rather self-contained, he is loved by many people.

He seems to have had virtually no bad reviews. One reviewer once wrote

of 'the Rev. Iain MacKintosh', an allusion to his almost priest-like

demeanour on stage, and then went on to speak of 'the Revered Iain

MacKintosh'. Maybe there was a grain of irony hidden away in this, for

on the other hand - on stage and even more so off it - Iain is known

as one of the best tellers of bawdy stories on the scene. Many of his

fans will remember their sense of shock when they first heard this

serious, quiet man who seemed like every mother-in-law's dream render

'Let's Do It', the 'Mermaid Song' or any one of his many bawdy songs

with that charmingly impudent grin of his.

One frequent topic among MacKintosh fans concerns the question: What

makes him the stage presence he is? The man is no banjo (or

concertina, or bagpipe) virtuoso - as he would be the first to admit.

His voice is agreeable, but not great. He is no eccentric in either

apparel or demeanour. During his concerts nothing happens. He just

stands there on stage, moves his fingers to play the banjo, moves his

mouth to sing, and uses facial expressions - sparingly - to project

moods. And yet, there is such a lot going on between him and his

audience.

I remember a conference of young 'greens' where Iain MacKintosh was

engaged to open for a rock band. Two hundred ecologically-minded teens

and twens were watching silently as a white-haired man in his late

fifties, clad in jeans and a blue pullover, climbed the steps to the

stage, banjo in hand. Applause was sparse, but when the second song

provided some semblance of an 'Irish' rhythm, some felt bold enough to

clap along. Before the next song, the man on stage, who must have

seemed fairly elderly to his young audience, looked around him and

explained gently, but with a wink, 'Listen, it's o.k. to clap along.

Just remember it doesn't fit every song!' There was no more clapping

along, whether fitting or not, but at the end Iain had to do three

encores and finally left the stage pointing out - typically for his

attitude to fellow musicians - that it would be unfair to let the rock

band wait any longer. His audience started a spontaneous collection to

pay for his hotel and asked him to stay on and do another gig to round

up the conference two days later. He agreed on the spot.

I remember a conference of young 'greens' where Iain MacKintosh was

engaged to open for a rock band. Two hundred ecologically-minded teens

and twens were watching silently as a white-haired man in his late

fifties, clad in jeans and a blue pullover, climbed the steps to the

stage, banjo in hand. Applause was sparse, but when the second song

provided some semblance of an 'Irish' rhythm, some felt bold enough to

clap along. Before the next song, the man on stage, who must have

seemed fairly elderly to his young audience, looked around him and

explained gently, but with a wink, 'Listen, it's o.k. to clap along.

Just remember it doesn't fit every song!' There was no more clapping

along, whether fitting or not, but at the end Iain had to do three

encores and finally left the stage pointing out - typically for his

attitude to fellow musicians - that it would be unfair to let the rock

band wait any longer. His audience started a spontaneous collection to

pay for his hotel and asked him to stay on and do another gig to round

up the conference two days later. He agreed on the spot.

At his gigs he avoids mickey mouse stuff and loudness; the stronger

the effect if he - very rarely - does turn up the volume. Usually,

however, he succeeds in getting his meaning across without raising his

voice. It is songs about social problems, injustice, or human

tragedies that give an inkling of the man behind the balanced stage

performer - a man who is very sensitive and capable of strong

reactions to the world around him, but also one who prefers to keep

his thoughts and feelings to himself. Off stage, too, he is not one to

argue or waste energy on, to him, fruitless debate. For the other

side, this can at times be rather frustrating.

In the same way, his simple, downright naïve air is only part of the

truth. The admiration he meets with still fills him with wonder, for

although he has a healthy self-regard he does not see himself as

someone special. On the other hand, he is sensitive to being

patronised or treated unfairly, and weighs the pros and cons of

starting a row about it. The usual answer is 'no', even if this means

financial loss, but he doesn't forget. Having said this, there are a

number of venues, mainly Scottish clubs, who can remember Iain waiving

his fee and saying, 'Give me what you can afford'. In Scotland in

particular, the music means more to him than personal gain.

In the same way, his simple, downright naïve air is only part of the

truth. The admiration he meets with still fills him with wonder, for

although he has a healthy self-regard he does not see himself as

someone special. On the other hand, he is sensitive to being

patronised or treated unfairly, and weighs the pros and cons of

starting a row about it. The usual answer is 'no', even if this means

financial loss, but he doesn't forget. Having said this, there are a

number of venues, mainly Scottish clubs, who can remember Iain waiving

his fee and saying, 'Give me what you can afford'. In Scotland in

particular, the music means more to him than personal gain.

This summer Iain MacKintosh turned 68. Recent years were not without

their problems. The death of Hamish Imlach in 1996 hit him hard. On

the other hand, he has formed a new musical partnership with ace

musician / songwriter and fellow Scot Brian McNeill which both seem to

enjoy hugely. It was never meant to be permanent, however, even though

they have made a CD together; a live CD will be coming out later this

year. Finally, after last year's big flu epidemic, Iain was discharged

from hospital with some friendly advice from his doctor to avoid

smoke-filled rooms.

He intends to follow this advice. From next year he plans to be at

home much more often, look after his family - not least his three

young 'grandweans' - and play only when he feels like it. In October

he will be doing a farewell tour of Germany, the country where (next

to his Scottish homeland) his art has been most widely appreciated.

Many people will miss his concerts where nothing ever happens.

Discography:

Albums:

- (A) By Request (1974)

- (B) Encore (1975)

- (C) A Man's A Man (1978) with Hamish Imlach

- (D) Straight To The Point (1979)

- (E) Live In Glasgow (1979)

- (F) Singing From The Inside (1981)

- (G) Home For A While (1984)

- (H) Live In Hamburg (1986) with Hamish Imlach

- (I) Standing Room Only (1986)

- (J) Gentle Persuasion (1988)

- (K) Risks and Roses (1991) CD

- (L) Just My Cup of Tea (1991) CD

- (M) Stage By Stage (1995) CD with Brian McNeill

Tracks on the following albums:

- Interfolk Festival vol. 4 (1973) OA, first appearance in Germany

- A Better Class of Folk (1974) OA, album of TV series

- The Greatest Ceilidh Band On Earth (1981) OA live at Tønder Festival

- Songs For Peace (1983) OA

- Freedom Come All Ye (1986) tracks from (E)

- I Was Born In Glasgow (1991) OA

- The Music & Song of Edinburgh (1995?) CD tracks from (M)

Session musician on the following albums:

Session musician on the following albums:

- Hamish Imlach Ballads of Booze (1967)

- Hamish Imlach Fine Old English Tory Times (1972)

- Hamish Imlach Murdered Ballads (1973)

- Gaberlunzie Freedom's Sword (1974)

- Gaberlunzie Wind & Water, Time & Tide (1976)

- Hamish Imlach Scottish Sabbath (1976)

- Hans Theessink Titanic (1981)

- Hamish Imlach Sonny's Dream (1985)

- Arthur Johnstone North By North (1989)

- Brian McNeill The Back o' the North Wind (1991) CD

- Rod Sinclair Breaks and Bonds (1992) CD

Photo Credit: All photos by The Mollis:

(2, 5, 9) Iain & Hamish Imlach

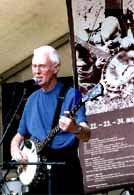

(3, 7) Iain at the opening of the 25th Tønder festival in 1999 in front of a poster of the 1st Tønder festival

(6, 11) Iain & Brian McNeill

Back to the content of FolkWorld Articles, Live Reviews & Columns

To the content of FolkWorld online magazine Nr. 15

© The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld; Published 08/2000

All material published in FolkWorld is © The Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors for permission.

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

I can't believe it's thirty years since three of us teamed up

I can't believe it's thirty years since three of us teamed up Some other special friends, of course, they know how I feel

Some other special friends, of course, they know how I feel This musical autobiography in five verses is one of the best-loved

items in Iain MacKintosh's repertoire. He claims to have written it

'within half an hour' when he turned sixty - to cheer himself up, he

says, and to remind himself of all the good things his life as a

travelling folksinger has brought him. (How just like him to maintain

a discreet silence on the downsides!)

This musical autobiography in five verses is one of the best-loved

items in Iain MacKintosh's repertoire. He claims to have written it

'within half an hour' when he turned sixty - to cheer himself up, he

says, and to remind himself of all the good things his life as a

travelling folksinger has brought him. (How just like him to maintain

a discreet silence on the downsides!)

He prefers not to remember his military service; however, it was here

that he was taught his first riffs on the guitar. In the late Fifties

he went to a Pete Seeger concert in Glasgow. The down-to-earth,

American banjo player who would even cut wood on stage if it served

his music made such a tremendous impression on Iain that he went and

bought a banjo. He had found his instrument. He joined the emerging

Scottish folk scene and discovered there were models to be found

nearer home: Alex Campbell who introduced Europe to British folk

music, Josh MacRae who got the first folk song into the charts with

'Messing About on the River', and that writer of both humorous and

overtly political songs, Matt McGinn.

He prefers not to remember his military service; however, it was here

that he was taught his first riffs on the guitar. In the late Fifties

he went to a Pete Seeger concert in Glasgow. The down-to-earth,

American banjo player who would even cut wood on stage if it served

his music made such a tremendous impression on Iain that he went and

bought a banjo. He had found his instrument. He joined the emerging

Scottish folk scene and discovered there were models to be found

nearer home: Alex Campbell who introduced Europe to British folk

music, Josh MacRae who got the first folk song into the charts with

'Messing About on the River', and that writer of both humorous and

overtly political songs, Matt McGinn.

Iain's professional work with the sadly missed Hamish Imlach turned

into a lifelong friendship, although - or perhaps because - this was a

meeting of absolute opposites: On the one hand the spare, quiet,

self-contained aesthete, careful with money, abhorring cigarettes and

hardly ever seen drinking; on the other hand the large, generous

bohémien who would freely admit his addiction to good food, alcohol,

nicotine and other people's company. As in life, this contrast had its

effect on stage when Iain and Hamish started performing as a duo.

Iain's professional work with the sadly missed Hamish Imlach turned

into a lifelong friendship, although - or perhaps because - this was a

meeting of absolute opposites: On the one hand the spare, quiet,

self-contained aesthete, careful with money, abhorring cigarettes and

hardly ever seen drinking; on the other hand the large, generous

bohémien who would freely admit his addiction to good food, alcohol,

nicotine and other people's company. As in life, this contrast had its

effect on stage when Iain and Hamish started performing as a duo.